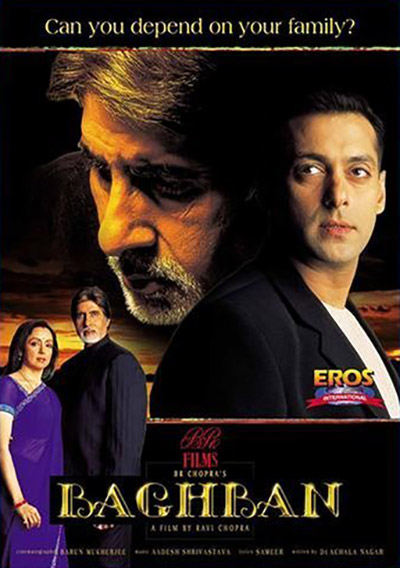

A poignant tale:

Raj Malhotra (Amitabh Bachchan) is a happy man. Close to retirement, he is fit and fine, jogs every morning, enjoys his work at ICICI bank, is respected by his colleagues and cherished by his friends. But the anchor of his life is his wife Pooja (Hema Malini), whose loving devotion to him is the source of his strength. She ties his tie every morning, keeps his tea ready when he comes home from office (opening the door even before he can ring the bell), and rests her head on the pillow of his arm every night to sleep. She is beautiful, and he is deeply appreciative of her presence in his life. In short, they are the very picture of a “happily married” couple.

They have four sons who have all grown up and gone away. The eldest has a young adult daughter, the second has a small son and a working wife, the third is newly married, and the fourth a bachelor. There’s also a fifth, the one he adopted, lifting him out of a life of poverty and enabling him with education enough for him to lead a prosperous life abroad.

So far, perfect. Problem starts when Raj Malhotra actually retires. He has a basic assumption about retired life: the belief that the ones he had nurtured with loving care will naturally look after him in old age. He is assured that he has “chaar anmol fixed deposits” in the form of his sons, whom he considers enough security for his old age. But the fixed deposits unfortunately turn out to be bad investments. When, during a family get-together in holi, their parents express a desire to live with them by turns, they reluctantly concede to the plan, but decide to split the parents between them.

What follows is predictable. The parents are not treated well – in not exactly the saas-bahu versions of extreme cruelty and vindictiveness, but post-millennial urban versions of insensitivity and singular unconcern. Raj faces new humiliations in the eldest son’s family every day: when he sits at the head of the table, he is asked not to; when he reads the newspaper in the morning, it is snatched away from him (because he will be at home and can always read later); when he types letters to his separated wife at night, the noise of the typewriter supposedly disturbs the daughter-in-law’s sleep. His only respite is the friendship offered by a Guijrati coffee-shop owner and his wife, Hemant and Shanti Patel (played by Paresh Rawal and Lilette Dubey, who for me are the best part of the film). The story on the other side is worse: Pooja gets the maid’s room to stay in and witnesses a dysfunctional household. The second son and his wife (Aman Verma and Suman Ranganathan) don’t seem to have much communication, are not aware of each other’s whereabouts, and are too lenient with their young adult daughter. When Pooja points these out, she is insulted. Later, Payel (RimiSen), the granddaughter, becomes close to her (just as the grandson had bonded with Raj in the other house), but Pooja misses her husband sorely. And after the first six months of their separation is over, Raj and Pooja decide not to prolong it any further and go back to living together like before.

In this they are aided by the sudden appearance of their adopted son in their midst. This London-returned son (Salman Khan) and his wife (Mahima Chaudhry) are exactly as they should be – grateful and full of reverence, who begin their day doing puja and end it by pressing Raj’s feet. In their house, the parents feel truly welcome. Meanwhile, Raj, urged by his friends, had been writing a novel based on his experiences, which becomes hugely successful and is awarded the Booker! In the award ceremony, he speaks eloquently about the isolation of old age and generation gap, publicly acknowledges only his adopted son, and refuses to forgive the other four. Even Pooja doesn’t relent when the sons ask for mercy. But they don’t shut out the grandchildren – “because there is no end”, says the closing caption.

Where are the other fathers??

Baghban is a tale told wholly in black and white – with a bunch of relentlessly scheming and selfish children pitted against a totally selfless pair of parents with an evergreen love for each other. But since one is supposed to willingly suspend one’s disbelief while watching mainstream Bollywood, one can – probably – dispense with the shades of grey and simply take visual delight in the gorgeous ageing couple. But even then, there would remain the haunting absences.

Raj Malhotra is squarely at the centre of the story. Fine. But is he the only father? I’m intrigued by the absent fathers in the film – who have been neatly edited out of the script. To begin with, what about his own father? How did Raj fare as a son himself? I am curious to know that. Too often parents expect from their children what they themselves have not done. The flashbacks show a young Raj and his wife’s kindliness to an orphan boy, but nothing about what they did for his parents. Did they all live together? Could Raj support his parents whole-heartedly in addition to fending for his large family with a single income? Probably he did. Or maybe, he couldn’t. Both are equally possible.

But more than the missing grandfather in the story, what is more glaring are the other missing contemporary fathers – the fathers of the four daughters’-in-law. Baghban is not a soap opera, only a three-hour movie. Hence, there is time and space for only one story. Granted. But the film could easily have two songs less and two scenes in their stead, where we could have been given just a little peek into the lives of other hapless ageing couples – the fathers of the bahus.

Let’s take the second daughter-in-law (as she is the only one who is sketched a bit; the youngest is given no separate scene, and the eldest is a cardboard character). Reena (Divya Dutt) seems to share a good equation with her husband Sanjay (Samir Soni); and most of her complains seem to have to do with tiredness, related to being a working mom. She doesn’t like the extra work that Raj’s presence entails for her, and she wants to sleep undisturbed at night. She makes that very clear – but in a very rude and insulting manner. Her father-in-law maintains a dignified silence all through, till he can’t stomach the little daily humiliations anymore and leaves the house.

As an audience I felt relieved that he did so, that he could keep his dignity intact. But I also wondered why Reena was always so irritated. Was it only because of the father-in-law? Or could there be other frustrations as well, in her life, which were never allowed to surface? What about her own family? I had many question marks there: Did she have a brother? Or was she an only child? If so, did she earn enough to be able to contribute to her parents’ well-being, their medical expenses? Did she ever have the scope to visit them and spend time with them? It’s quite possible that the answers to all these questions could somewhere add up to her irritation.

At one point, we see her telling a friend over the phone that she has more burdens now. Did she ever call her mom to say the same thing? After all, it is usually to mothers that married women confide the most. I would have loved to see that scene! Chances are, her mother would have given her that timeless Indian advice for solving all family problems: namely, to “adjust” to the situation and “maintain the peace” of the house; or probably she would have persuaded that the presence of a grandparent is good for the grandchild; or may be, the mother had a sharp tongue, and said that the elderly Malhotras should have had only daughters instead of sons – they would have had less expectations then!

Chances could even be that Reena’s father and father-in-law actually got along very well, whenever they met; and that on a chance encounter, over a cup of coffee, they realized that they were both equally unwanted by their children. That would have made the pain and hurt felt by Raj and Pooja far more realistic and memorable for me. As it stands in the film, it’s a uni-dimensional story, their life and struggles taken out of a broader social context.

Fathers of daughters:

Baghban is not just about any father – it is resolutely about the SON’s father. And the claims – to the son’s time, attention, support, understanding, and love – that he rightfully has in that capacity. The rights of the son’s father are very forcefully articulated in the film. But it is about time filmmakers remembered the fathers of daughters as well: that they too age and ail, face loneliness, and financial loss, and can be unwanted and bereft of friends.

On ‘Father’s Day’, I hope the fathers of daughters are not edited out of the script of their lives; and I hope more filmmakers (apart from Soojit Sircar) choose to focus on them and the special father-daughter bond in the near future.