When Rituporno Ghosh died suddenly on 30 May 2013, I felt a deep sense of personal loss. I had never known him, never met him, he was not related to me in any way – and yet, I cried as much as I had when Satyajit Ray had passed away during my Higher Secondary Exams in 1992 and Ma had tried unsuccessfully to keep the news from me. I had grown up with Ray’s films; with Ghosh, the association was very different.

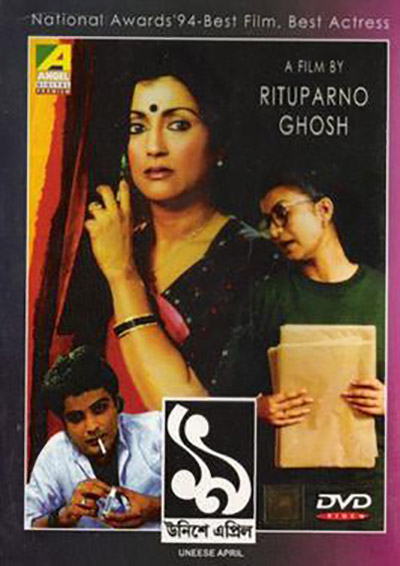

When UNISHE APRIL released in 1994, to universal acclaim, announcing the arrival of a talented new Bengali filmmaker, I was in college. And soon, I made it a point to see the film. What had initially intrigued me about it was that it was about a complex mother-daughter relationship; and after watching it, I realized that I had never seen anything like it on Indian screen before – a nuanced exploration of a filial relationship, with two female leads. The nuanced exploration of (all kinds of) personal relationships would become his signature style, as would having predominantly female (instead of male) leads, and the use of natural realistic dialogue. All of these reasons made me eagerly look forward to his work.

I was very used to watching films with my friends in college. We would collect small change and walk all the way from College Street to Esplanade to watch a BASIC INSTINCT or a 1942: A LOVE STORY (there were many others… can’t recall the names now). But my longest film-going companion had been my mother. All through school, every year, she would treat my sister and me to a film after our Annual Exams; mostly taking us to theatres that were closer to our place, either in Lake Town (Jaya/ Mini Jaya) or Shyambazar (Minar). That ritual actually continued well into our graduate years – hence, it was a natural choice for me to watch UNISHE APRIL with Ma. For more than a decade since then, I made a new rule for myself: I reserved Bangla films for her; while I enjoyed Hindi and English films with friends (and increasingly, with my ‘boyfriend’).

My life underwent tremendous changes during that decade – soon after my Masters, I commenced work on my Ph.D, got married (to my boyfriend!), started living with his family, joined an undergraduate college as a full-time lecturer; my sister left Kolkata to work in B’lore, my husband left to work in Chennai, my closest friends left to study in the UK and US. Only I was left behind, and the only thing that didn’t change for me in a fast-transforming Kolkata was going out and watching a Bangla film with Ma now and then – during the weekends that I spent with them. And often enough, the films happened to be by either Rituporno Ghosh or Aparna Sen. We would watch a film and then invariably come home and have long discussions about it. I particularly remember DAHAN (which remains my favourite Ghosh film till date), BARIWALI, ASUKH, TITLI, RAINCOAT, and PAROMITAR EK DIN (this last by Sen).

When Ghosh died, I mourned his loss deeply: it was so deep that I was myself taken aback by its intensity. I realized later that the pain I felt then was not just for a great filmmaker who had died at the height of his powers, leaving an irreplaceable loss in the film industry; that patriotic mourning for the loss of a national treasure was not what it was all about. The source of the pain actually lay elsewhere: with his death, I felt I had lost a part of me, a part of my past – forever.

Great artists (be it writers or filmmakers or singers) just don’t entertain – they become a part of the texture of one’s life and get inextricably tied up with one’s personal memories. So has Ghosh been in my life: his films are inextricably tied up with the memory of one of the greatest pleasures of the life I’ve left behind me in Kolkata – going out for a film with my mother.