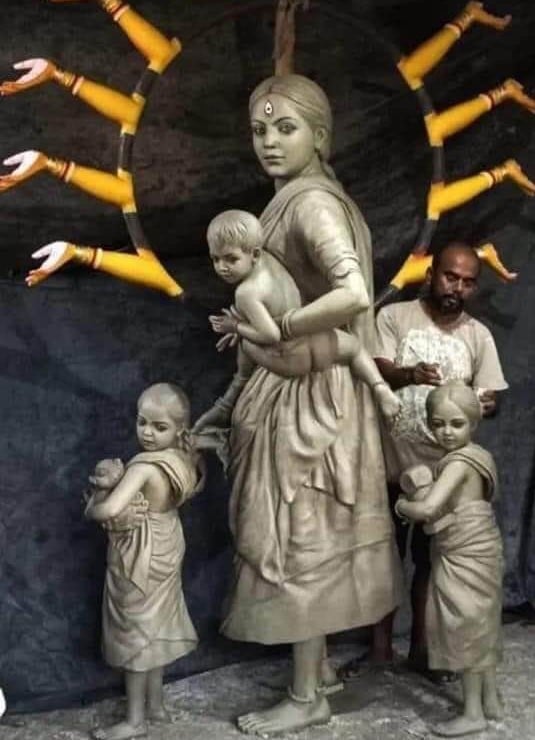

A full seven months into the pandemic, I have realised a new reality in India. While migrant workers have been the hardest hit, some of their cohorts in the city have done well. This realisation came in the wake of the powerful image that went viral yesterday – of Ma Durga as a migrant worker with children in tow, by the artist Pallab Bhowmick.

By ‘cohorts’, I’m referring here to the daily migrants who commute to the city from the suburbs by train. When the first lockdown was announced in India in late-March this year, they were distraught, because it meant they would lose their daily wages. With successive lockdowns in the next few months and train services closed, their livelihoods were threatened. However, there were at least some who managed not only to survive, but didn’t face any trouble at all, as they were given paid leave by their employers. Which is how it should be. I know because we are one of the employers who did so, as have many others of my acquaintance who hire domestic staff – help, cook, nanny, nurse – from ayah centres; workers who are paid by the hour, and whose rates are way higher than local helps (as a certain percentage of what they earn has to be given to their centre).

Domestic circus since 2017

These ‘centres’ have been my lifeline since autumn 2017, when I started living with my widowed father after returning from Amsterdam. He was already living alone for a year then. And my mother’s absence had been replaced by a bunch of domestics – day help, cook, someone who did the grocery, and a part-time driver. After I returned home with a child, a nanny was added and a full-time driver engaged. And after my father suddenly fell ill with a kidney problem just a few months later, nurses had to be included to this ever-increasing group: two at the beginning for a few months, when Baba was bed-ridden at home after six weeks in hospital; and then one, when he slowly got back on his feet again. At some point, the previous domestic help doubled up as the night nurse (I will call her S).

To co-ordinate this staff daily has itself been a full-time job. There isn’t a single week when someone or the other is not absent or doesn’t have a problem. They are all people with families, after all; and most of them being women with children, they are often left at the mercy of vagaries at home. And I, in turn, am left at their mercy. I’ve often felt that my teaching is actually a secondary activity: my real ‘job’ is to keep this staff going.

In the first year after my return, I lost count of how many people joined and left: there were three of Srishti’s nannies who followed each other in rapid succession & Baba’s day/night nurses changed up to four times (if I remember right). I also lost count of just how many times a day the door had to be opened… ‘coz there wasn’t a single hour when the calling bell did not ring. Between them, from morning 7 to evening 8.30, our house staff constituted a long chain of arrivals and exits (7 am -12 noon being the peak time) – one coming as the other prepared to leave, some overlapping; and interestingly, managing to have, even in those small pockets of time, some very spicy relationships, rife with jealousies and rivalries, tiffs and showdowns. TV soaps paled before them!

When Baba was alone, nobody (in the then smaller staff) was ever absent. They had great concern for this 80-year-old man living all by himself, who was still agile and active, and who really didn’t need much looking after. Their workload was also less, as there was little to do in the house. But things changed after I came to stay, with a child. Their absences increased, for one – especially the cook’s; and the dynamic at home also changed. Drastically so, when Baba was taken ill. All through this, S remained the most reliable worker at home & continued to be so till March 2020.

White collar slavery

During the lockdowns, none of our house staff could come. While we gave paid leave to all, our need of them were not the same: while the driver was not required at all (since we weren’t going anywhere) and the nanny could also be done without (as I was at home), the cook and the day help-cum-night nurse were very important for us. After two months of paid leave, we asked the latter – S, that is – to stay with us. That way, she could easily maintain her job and I would be spared the tremendous workload that had befallen me. She was used to spending more than half the day with us, anyway. We suggested that for the next few months (things were still very uncertain), she just extend that and make it full-time work. She accepted it rather reluctantly. Her father died suddenly soon after, so she left again to be with her bereaved family. We thought she would return after the ‘sradh’ ceremony, but she didn’t. She had left for good.

She was with us for only a fortnight. All the while restless, unhappy. She was free for half the day, could call her sons anytime, see them everyday, but I could sense her restlessness… though I had never expected that she would leave without notice. Her father’s sudden loss we respected: giving her 14 days off soon after she joined. And then waiting for her return. June went in waiting and hoping for her return. I have waited for few people in my life the way I waited for her in June – both for Baba’s sake and mine.

Who leaves a secure job at a time when so many others are losing their incomes? It can only happen if an alternative source has been arranged for. She said she can’t live without her sons. But none of them do any work: they were both looking for one, the last I knew – one after graduating, the other after not having finished his degree. The three of them living happily together for months with no food on the table made no sense. A plan B was obviously in place.

I find people in white collar jobs faring far worse. I know of experienced journalists who have been unceremoniously sacked; part-time teachers who have not been paid for months; IT professionals who have had massive salary cuts. In my family, salaries have either been slashed, or late in coming, or both. I also know that nobody among my friends/acquaintance is even dreaming of greener pastures, because there aren’t any. People are simply holding on to their jobs, even the ones that pay abysmally, because losing it would be worse.

Among our house staff, the most reliable one left (who worked for two); the (in any case frequently absent) cook is only waiting to go back to her family in Bangladesh (which she has been doing since she lost her brother last year); the nanny (the most well off among them) has ‘decided’ she won’t work during the pandemic (as she is saddled with everything at home – kid, in-laws, house-work); and the driver (the most needy of them all) has come religiously right at the beginning of every month to claim his salary with what can only be termed ‘swag’! I am the only one among them who both needs my salary and has to work to earn it every month.

Glad…

I gave S two relaxed months. I’m glad about that: they were the only in her life. When mornings were spent having tea at different neighbours’; housework and lunch completed, post lunch was time for ludo, picnic style – lying on newspapers, under the shade of a tree, munching on savoury delights; and evenings were devoted to cooking her sons’ favourite dishes (this part she loved, as they could never have dinners together while she worked). When she recounted her blissful lockdown weeks with evident relish, I would recall the frantic, feverish ones I’d had – paying her and doing her work, and those of others. In addition to mine, of course.

My friends, family members and I have had to work more during the pandemic – no matter which profession we are in. We worked more, got the same or less or late salary, or were sacked. And here she was, talking about lazy afternoons full of ludo and cucumber salads and tamarind chutneys. I didn’t say anything to her… was just relieved that she was now with us. Mostly for Baba’s sake.

Feeling betrayed

Baba is always kind to a fault and generous with financial assistance to needy people. And I haven’t known a more compassionate man than him when it comes to domestic helps. His care and concern for them far outstrips what they do for him or the house. This is especially so with the ones who came in his life after Ma’s death: he would insist on buying Women’s Horlicks for them, and tears would well up in his eyes speaking of the injustices they have faced in life. He was extremely fond of S, looked on her like a daughter (she also happens to be exactly my age). He also relied on her a lot; no one was happier than him when we decided to bring her home to stay with us. Having worked for him since 2016, she knew his routine inside out: what he ate, what he wore, his medicines, his idiosyncrasies. He would chat with her while she worked, she would scold him for being unreasonable sometimes. We looked upon her as a family member, and were both partial towards her – because she was sincere in her work and also chipped in when others were absent.

I have always looked upon the women who have worked for me as co-workers, because their work in my home have enabled mine outside it. Over the last three years, S was the one who had been witness to my daily challenges, and helped me navigate it; I gradually came to look upon her not only as a co-worker, but a friend. One of my earliest posts in my blog was about her: that is the respect I accorded her and her life. At the end of each day, we would sit and chat – two working mothers, with different-aged children. I genuinely thought she would continue working for us: she was good at her job and earned a substantial income. I thought it worked well both ways, that the comfort level was on both sides. I was wrong. Turned out… we were just another employer for her!

The positive side

I tried to see the positive side of things after she left. To begin with, because of her, I could go out of the house three precious times, which I wouldn’t have otherwise. Never mind that they were to the police (local PS & then to the Head of Traffic, Lalbazar), to the doctor (more than once actually), and to bring her. The first two were for permissions, the third to ensure that she had a safe passage from her home to ours. The day I had chaperoned her, I had felt a real sense of achievement! I had fallen ill in May… out of sheer exhaustion, but this had to be done. And a whole excited week went in arranging to bring her back.

After she left, from July on, with Srishti’s new session in school and my new teaching semester at college in full swing, my work increased manifold. But I didn’t fall ill from exhaustion any more… because I realized that’s not an option available to me. The other truly positive thing that emerged out of this situation was that both Srishti and I became more self-sufficient: I simply morphed back to an earlier self who was used to doing compulsive domestic work; while Srishti learnt to bathe and eat lunch herself!

Enabled few

Four months down the line, I see this issue even more differently. To return to where I began: the powerful image of Ma Durga as migrant worker… it is good to see that at least some workers have options and can exercise their right of choice. That they are paid according to their experience, with mandatory increment every year – as per their experience, expertise and working hours. They get paid leave, and they leave good employers to work for better ones. And they have the confidence to do this during a pandemic. Because they know their services are required.

I am happy that at least some women are having it good – after years of struggle. May their tribe increase!