Jatugriha literally translates as ‘the burnt home’, and indeed, what is remarkable about the film is the way in which it delineates marital discord. It was a unique Bengali film of its times, and remains so even after 50 years!

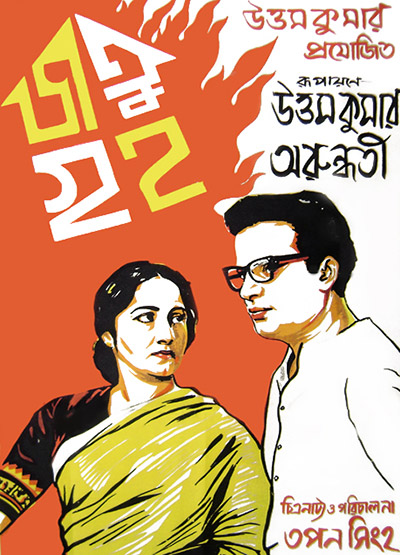

Jatugriha was released in 1964 – the same year as Ray’s Charulata – and marks a mature high point in the careers of all concerned: the leads Uttam Kumar and Arundhuti Debi, the supporting actor Anil Chatterjee, and of course the director Tapan Sinha. With such an amazing bunch of creative people coming together in the film, little wonder it turned out so well. It is useful to remember here that by 1964, Uttam Kumar was not only Bengal’s undisputed matinee idol, but also a successful producer with two acclaimed films to his credit. Jatugriha was ‘Uttam Kumar Films Pvt. Ltd.’s third venture and it attested the star’s commitment to quality films; films that somewhat extended the scope of commercial Bengali cinema.

Jatugriha had an ace director and a talented cast, but its chief strength was its story. Subodh Ghosh’s stories had already proved very successful on celluloid – both Bengali and Hindi -among others, in Ritwik Ghatak’s Ajantrik (1958) and Bimal Roy’s Sujata (1959). Tapan Sinha added one more memorable film to the list. Another USP of the film was the lead pair.

When talking of Uttam Kumar, Suchitra Sen’s name is never far behind! Bengalis are prone to talk of ‘Uttam-Suchitra’, the brand, rather than the actors individually. Indeed, they did 27 films together in a span of two decades and left a permanent mark in the history of Bengali cinema. But Uttam did a sizable amount of films with other co-stars as well. Of them, the ones with Arundhuti Debi – including Bicharak (1959), Jhinder Bandi (1961), and Jatugriha (1964) – were a class apart. They were based on literary classics, directed by Tapan Sinha (Arundhuti’s husband) and dealt with unconventional themes. And though they were the lead pair in the films, they did not play stereotypical ‘romantic’ roles in them. Uttam Kumar had once remarked that he changed his acting style with every co-star; with Arundhuti, he adopted a more intellectual style to match hers. It is very much in evidence in Jatugriha, where they play a couple in – and out of – love, without an iota of mushiness.

Marital discord

The title-credits of the film open to Supriyo (Anil Chatterjee) negotiating the rain-splattered streets of Calcutta. He is the ‘kerani’ (clerk), doomed to a tough existence in a big city. For the affluent, it is a different matter; they return home in cars – like Shatadal Dutta (Uttam Kumar), a very successful and high-ranking officer at the Archaeological Department of the Government of India. He picks up his friends’ son from the street, walking in the rain because his parents failed to turn up at school. They are too busy fighting, as it turns out, when Shatadal drops the boy home. He is offered tea by the flustered couple, but he refuses, pleading exhaustion. These opening scenes – with the boy (whom Shatadal is evidently fond of) and the acrimonious couple, set the scene for the central theme of the film. We would see another (less acrimonious, though equally painful) kind of marital discord unfold in the next 90 minutes, and that would stem from the lack of a child.

The very first scene of Shatadal with his wife Madhuri (Arundhuti Debi) speaks volumes about their crumbling marriage. After dropping little Samik at his home, Shatadal returns to his own, and in a tired voice asks Ramu, the servant, to give him tea. He has the tea by himself; then calls up his advocate who wants him to bring false charges of infidelity against his wife to make his case ‘stronger’. He refuses to do that, but is quite clear about wanting a divorce. He then sits alone in the dark, with the music of a night club playing outside his window. (This would become a motif in the film – a motif of the loneliness of modern life and alienation in the city). Madhuri enters the bedroom after a while and goes about doing this and that. Asks him why he is sitting in the dark. He mutters something; and so does she, about rains in Calcutta and the inconvenience thereof. They are making small talk, not conversation. He leaves for a film, once again alone – saying, he will be late and have dinner outside. She should not wait for him. She says “OK”, without even looking at him, as if this – his going out on his own immediately after she returns home – is the most natural thing in the world. There is no anger, irritation, or hurt in her voice – only a studied indifference. And yet, she is still the perfect homemaker. After he leaves, she asks Ramu whether his shirts have been given to the laundry; opens the fridge and seeing no eggs and fruit for next day’s breakfast, instructs Ramu to bring that first. After having said, in an emotionless voice, that Ramu can just make something for himself for dinner, as they would not eat. The most common and pleasurable ritual of domesticity – having tea and dinner together, and the sharing of lives and the day over the dinner table, does not exist for them.

They have breakfast together before going off to work, but it is fraught with tension and suppressed anger. He is furious about missing papers; she is eager to maintain a semblance of normalcy before little Samik, who habitually drops by, preferring to be with them than his own parents. Little does he know that the same dynamic of marriage plays out here as well, with the couple he thinks to be ideal! The audience knows better – that Madhuri is bound by duty to Shatadal, not love. She is desirous that he have his medicine on time, but makes it clear that she has absolutely no interest in their new house that is nearing completion.

The house that could not be a home

But things were very different when work had begun on the new house. It was to be their dream home and she was full of interest and excitement; he too, with his architect’s sensibility, could not stop thinking and planning about the house. He complied with all of Madhuri’s demands about the house – a kitchen-garden, a bathroom that she would design, a study for him; and also added his own – a nursery for their future child. He even drew in Samik in his plans, telling the boy they would have a huge verandah in their house from where, when they were old, they would see a grown-up Samik whizz by in a big car! The house epitomized their future – their future together – which seemed so full of promise; and yet, in the course of constructing it, that promise fizzled out, and their interest in the house dwindled with the growing distance in their relationship. In the crowning irony of the story, their marriage broke when the house was finally built!

Interestingly, the house gets built even as the film progresses, with scenes of its construction dotting the narrative. The audience thus gets emotionally invested in the house in the course of the film and feel a pang of loss when Shatadal decides to sell it off immediately after its completion. He first offers it to Supriyo (Anil Chatterjee) as a gift, as he had grown genuinely fond of this young clerk and his impoverished family, but Supriyo declines his generosity with great dignity. He sells it eventually, but the audience is spared the sight.

Shatadal & Madhuri

What went wrong with Shatadal and Madhuri? Their marriage, like most marriages, (at least in the India of the 1960s) was premised on a future with a child. Sadly for them, Madhuri was diagnosed as infertile; and while Shatadal tried his best to take this reality in his stride, Madhuri was unable to accept it. Thereafter (as Shatadal later tells his friend Nikhilesh), “Madhuri started thinking she is incapable of making me happy, and I too failed to understand her… may be, I didn’t try enough. And then I saw I’ve made the office my home. Life seemed meaningless. So, we wanted to make an end of it.” What started with “poetry and dreams” ended in divorce.

It may be noted that the film is narrated essentially from the man’s perspective. The marital discord is shown to us from the couple’s interaction with each other, but we get more of his side of the story than hers. Though Shatadal tries to initiate the process of divorce, it is Madhuri who takes the decisive step. She just leaves him one day. What the discord was doing to Shatadal, we get to see – his changed attitude to work, his brusque behaviour with his colleagues, his irritation at home, his impatient interactions with labourers engaged in the construction of his new house. And when it is over, we also get to hear his side of the story. Incidentally, he sums up his marriage to his friend in the same darkened bedroom that we see him at the beginning of the film, his loneliness accentuated manifold by the same merry music of the nightclub playing outside his window.

That scene remains in the viewer’s mind long after the film is over. No equivalent scene is however given to Madhuri. We do not get to hear her or see her ‘going through’ the painful process of separation. She is young, beautiful, confident, independent-minded, and forthright; according to Nikhilesh, she is also “polite, patient… an angel” (in sharp contrast to his own constantly bickering wife, ie). She does not lose her temper ever; only once does she raise her voice to Shatadal’s, for which she promptly apologizes. There’s a certain elegant restraint in her personality, which was a welcome relief in the depiction of women in the Bengali commercial cinema of those days, where heroines were mostly drooly eyed and sentimental, either crying or singing romantic songs. Madhuri does not drool over her handsome husband, even in their happy days – even when she expresses her gratefulness to him, for his presence in her life and for gifting her a beautiful house in Calcutta.

She is independent-minded, but very conventional in one aspect. She feels awfully guilty for not being able to give a child to her husband, and joins a school only after coming to know of her infertility. Not before. In fact, she says to her husband (in the longest scene of argument between them in the film) that, like most women, all she had wanted was a home and domesticity. Hence, the lack of a child was particularly painful for her. He being a man had his work, office, and other interests of the outside world to distract him. She had none. Again, when they meet accidentally after seven years and is asked by Shatadal why she did not marry again, she says: “What I couldn’t give you, I won’t be able to give any other man as well. Knowing that, there is no point in getting entangled with another life.” It does not occur to her that marriage can be just for companionship, even without children, though she herself recommends it to her husband: “Please marry,” she tells him as a last request, “a man cannot continue like this.” And a woman can? – one is tempted to ask her. She speaks candidly to Shatadal of her own loneliness, but then, buys into the patriarchal logic of the privileges of men.

One wonders whether the particular marital discord showed in Jatugriha was just a problem of conditioning and not relationship per se; that the marriage could have been saved if Madhuri had not internalized gender stereotypes about marriage and motherhood. However, what stays with the audience is not so much the couple’s pain for childlessness as the pain of their growing distance, their increasing lack of communication and separation. This is essentially a film about falling out of love. And its poignant residue, which the couple experience when they meet accidentally in the waiting room of a railway station, seven years after they parted ways. During that short time, as they catch up on their lives, Madhuri effortlessly slips back into the role of the wife, feeding Shatadal and fussing over him. They even share humorous stories of their past and laugh together. All of a sudden, a decade seems to melt away… but the train whistle jolts them back to their reality. They board their separate trains going in different directions, but again face each other across windows. In their final exchange, she says, seeing him after all these years, she feels tempted to go back to him, to try again… but she won’t, as what separated them before would stand in their way again. It was better this way…. Her train zooms past while she says this, tears in her eyes, with the man who was once her husband trying to absorb the finality of their separation. By way of symbolism, we are shown a waiter hanging a pair of perfectly matching cups at two ends of a long line of crockery.

I had started by mentioning that Jatugriha was released in the same year as Charulata. The latter is an internationally known classic, partly due to Ray’s stature in the West; Jatugriha, on the other hand, has almost dropped out of public memory. This post is a humble attempt to resuscitate it.