Storyline:

A photographer (Mahender/ Naseeruddin) and a school-teacher (Sudha/ Rekha) get engaged, but not by their own choice. It is brought about by his uncle (Shammi Kapoor) who is also her mentor. It HAS TO BE honoured, even if the man is in love with another woman. When marriage is thrust upon him, Mahinder says it all to Sudha – who asks him to do what he thinks to be right: that he should take his beloved to his uncle and confess his love. The old man would surely relent. Mahinder is all gratefulness and rushes back to his lady-love (Maya/ Anuradha Patel), who is a lovable scatter-brained girl, frequently given to vanishing, a habit begun while trying to fly away from unloving parents. They ‘live together’, but in this instance, just when he most needs her presence (so that he can take her to his uncle), she has vanished again. When she returns, it is too late – the marriage has already happened by then! But a lot of her belongings remain – a perpetual reminder of her former presence in the house. At one point, Sudha tells Mahinder: “I feel as if I’m sharing everything with another woman. There’s nothing in the house that is truly mine”. He reasons: ‘We’re both tying to live without each other. I have you, Maya doesn’t have any one”. Another time, he says, “You can’t forget her even more than me”, and urges her to leave “the past (his past with Maya, ie) behind”. But he is himself unable to do it, partly because of Maya’s constant missed calls and surprises. They go on a honeymoon pledged to begin a new life; they return to a Birthday bouquet sent by Maya. Just when they are poised on a new understanding, a distance grows between them, owing to Mahinder’s secret meetings with Maya, which leave tell-tale signs – “lipstick on a shirt, a pair of ear-rings”. Sudha leaves.

What she does not know is that Maya had actually attempted suicide and Mahender felt obliged to look after her. But he did not want to divulge this at the moment and hence, met Maya secretly. He is cruelly divided between the two women, trying hard but unable to make things work. After Sudha leaves, he has a heart-attack; and Maya returns to the house to nurse him back. It is during this time that Sudha calls him once and Maya answers the phone. The couple had not met or called in between, and Sudha assumes that Maya has come back in Mahinder’s life for good. Sudha now makes up her mind: explaining to the uncle that Mahender has never misbehaved with her, has been honest; and if he could sacrifice his love for his uncle, then the uncle should also give in to him now and let him be with the woman he loves. Besides, this is really the only way out; otherwise, none of them could live in peace – neither she, nor Maya, nor Mahender.

But all this is told, explained, in the waiting room of a railway station – where the former couple accidentally meet after 5 years. Sudha’s mother had passed away in between and she had started wearing glasses. Mahender however remained as unorganized as ever! The biggest shock for Sudha is the news of Maya’s suicide. She comes to know that when Mahender had got the divorce papers from her by post, he went mad… and shouted at Maya. In retaliation, Maya, ever the impulsive one, just took out his bike and rode into the night… and to her own death. So he lost both women – to divorce and to death. Sudha had married meanwhile, just a year before – but this information is withheld till the last moment. The audience is as much surprised as Mahender when this is disclosed; and the utter desolation on his face when he sees Sudha’s husband (Shashi Kapoor in a guest appearance) constitutes the poignant climax of the film.

The first time Sudha had left Mahinder suddenly, without notice. This second time, on their chance encounter in the waiting room, she however takes his ijaazat – permission – to leave, and bids him a tearful goodbye.

Hindi Remakes of Bengali Films:

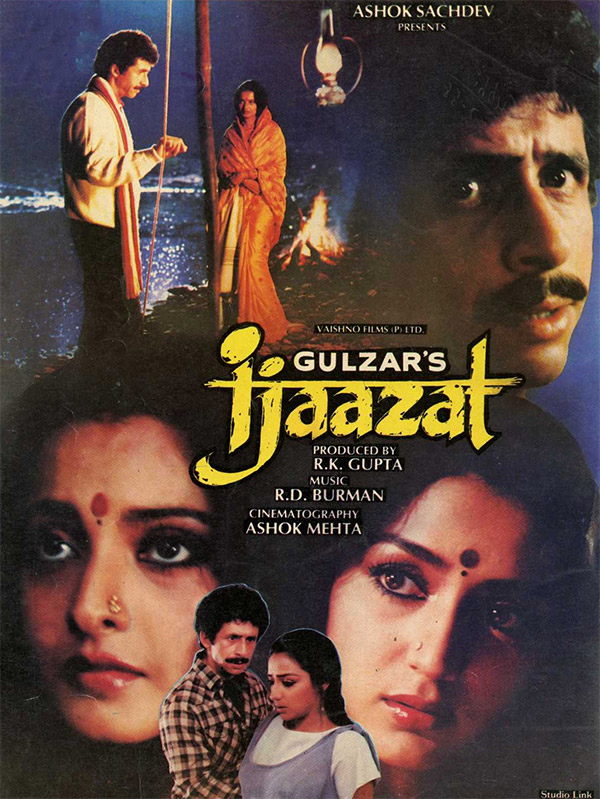

Ijazaat (1987) was a Hindi remake of a Bengali film – Tapan Sinha’s Jatugriha (1964), based on a story by Subodh Ghosh. Coming 23 years after the original, this film catered to a different generation of audience. The filmmakers were however contemporaries – though they begun their careers in different decades, they were creatively active for a long time together. Gulzaar was not a Bengali, but he was trained in the direct line of great Bengali directors who had made it big in Bollywood – he began his career as an Assistant to Hrishikesh Mukherjee, who in turn, learnt his craft from Bimal Roy. Like them both, he frequently used Bengali stories and actors; and in this case, remade a Bengali classic in Hindi.

Hindi films based on or inspired by original Bengali ones were not a new phenomenon. It happened at regular intervals; and it may be noted that Tapan Sinha was a particular favourite when it came to these remakes – Hemen Gupta remade his Kabuliwala (1957) in Hindi (1961), with Balraj Sahani in the lead; Gulzaar’s own directorial debut Mere Apne (1971) was a remake of Sinha’s Apanjan (1968). Later in the 70s, there was a new development in this trend when Shakti Samanta simultaneously shot Hindi and Bengali versions of his films Amanush (1975) and Anand Ashram (1977), with Uttam Kumar in the lead. Ijaazat broke new ground in this genre in the late 80s by differing significantly from the Bengali original.

Two time-tested Bollywood formulas: ‘Parental opposition’ + ‘The other woman’

The chief difference between Jatugriha and Ijazaat is that, while in the Bengali film, the couple separate/ become distant from each other because of the lack of a child, in the Hindi film, it is ‘the other woman’ that causes the rift. It is the continued presence of his former love in the life of Mahinder – and hence in the life of Sudha – that their marriage breaks. Both try their level best to make it work, but Maya keeps coming back, keeps coming between them. She was never gone in the first place. In a way, it is actually ‘parental opposition’ that is the real culprit in the film. Hence, Ijaazat actually follows two time-tested Bollywood formulas, tying them both in one plot – parental opposition + the other woman. In fact, here, it is because of parental opposition that the beloved becomes the other woman. Just like Silsila, where, due to familial obligation (the man marrying his elder brother’s fiancé after his sudden death), the beloved had become the other woman – but while in Silsila, she comes back accidentally in the married man’s life, in Ijaazat, she is always there, looming on the horizon. (Incidentally, Rekha plays the wife here; she was famously the beloved in Silsila.)

There is actually nothing inherently wrong in the relationship of the married couple in Ijaazat. In fact, they enjoy each other’s presence and laugh together a lot. There is a certain easy familiarity about them that is not common in the depiction of arranged marriages on screen. There is also a certain romance in their relationship, as they live with each other- an easy friendly romance, not heavy with passion. Hence, its depiction is also easy and refreshing: no drenching in the rain or dancing around trees or smouldering passion before a fire. There is the beach and the stream, the woods, and a warm embrace in the honeymoon song; no wet red chiffon, only a luminous Rekha clad in beautiful cottons.

There is also no melodrama – in gesture, word, or song. You don’t expect that in a Gulzaar film, anyway – what you do expect is plentifully there: subtle evocations of complex human relationships, expressed in pithy dialogues and beautiful lyrics. The best song is sung by Maya in the film:

Mera kuchh saman tumhare pas para hain,

Saavan ke kuchh bhige bhige din rakhe hain,

Aur mere ek khat mein lipti raat pari hain,

Woh raat bujha do, mera woh saaman lauta do.

This she writes to Mahinder when he sends her remaining belongings to her by his servant. Can he return everything – wet rainy days, a letter-wrapped night? How could their time together be erased? Memories can’t be returned; they remain.

All through the film, it is difficult to take sides. Like Mahinder, we too oscillate between Maya and Sudha – Maya’s spontaneity, her pain of being betrayed by Mahinder and yet, her inability to let go of him; Sudha’s mature understanding and her hurt pride of always coming second to Maya in her husband’s affections. Mahinder’s predicament, however (as we have seen), is the worst of all – he cannot stop loving Maya, but he also desperately tries to build an honest relationship with Sudha and is attracted to her in a different way.

Three young hopeful lives are thus messed up- and all because the elders had to be appeased! All because an engagement was thrust upon two unwilling people, despite one being in love with another woman and having ‘lived with’ her (by no means a common thing in India of the 1980s).

So, this film is ultimately about love, and not marital discord. More precisely, it is ultimately about the love that cannot be accepted by parents, and the life that is made unhappy due to parental opposition. Individual happiness surrendered to the tyranny of elders! A marriage date is suddenly fixed by elders – and the date has to be honoured, not the love relationship between two adults. It cannot wait a few more weeks, by when Maya would have surely returned. And why do Mahinder and Sudha marry? He marries to appease his uncle; she marries to relieve her widowed mother of her constant anxiety about her future.

By 1987, Gulzaar had already established his signature style of making unconventional films staying within the mainstream (Koshish, Aandhi, Mausam, Namkeen). But in this film, at least, he does not go beyond Bollywood’s time-tested formulas – though this is not apparent at first. It struck me only this time, when I watched it after 20 years!

When I first saw it, I had found the ‘live together’ very bold and the honesty of the husband attractive. And I was just bowled over by the songs. They remain my all-time favourites!