Ritwik Ghatak & Partition

India’s moment of liberation from the British was also a moment of rupture: with independence came partition on 15 August 1947, in what was one of the greatest ironies of 20th century history. Partition did not mean quite the same thing for Punjab and Bengal – the two provinces that got divided on the eastern and western borders of India – but there was one aspect that was common to both: most ordinary citizens found it difficult to accept the fact of partition and their lives changed beyond recognition once they became refugees.

And yet, as far as Bengal was concerned, Partition hardly had any immediate thematic impact on film or literature. The first Bengali novel to deal with partition came out only in 1955 – Narayan Sanyal’s Bakultala P.L.Camp. But it was highlighted on celluloid much earlier – in the 1950 classic, Chinnamul (“The Uprooted”), by Nemai Ghosh. This landmark film, which ushered in Bengali cinematic realism, relates the story of a group of farmers from East Bengal who are forced to migrate to Calcutta because of Partition. Ghosh used actual refugees as characters and extras in the film, but there were some seasoned theatre actors in the cast as well. One of them was Ritwik Ghatak – who would soon turn director himself and make the partition theme his own.

Ritwik Ghatak’s films are one of the most powerful artistic articulations of the trauma of displacement consequent upon partition. The cultural unity of the two Bengals was an article of faith with him. He never accepted the Partition of 1947 and it became an obsessive theme with him.

In a cinematic career that spanned over 25 years until his death in 1976 at the age of 50, Ritwik Ghatak left behind him eight feature films, ten documentaries and a handful of unfinished fragments. But he is remembered mostly for his feature films today. Recognition came his way very late and he had the misfortune of being largely ignored by the Bengali film public in his own lifetime. This was particularly unfortunate; as Ghatak was one of the most innovative of all Indian filmmakers, developing an epic style that uniquely combined realism, myth and melodrama in many of his films.

Before he came to films, however, Ghatak had been involved with the IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association), the cultural wing of the Communist Party of India, which, since 1943, led a highly creative movement of politically engaged art and literature, bringing into its fold the foremost artists of the time. IPTA had a profound influence on Ghatak. True to its credentials, he strongly believed in the social commitment of the artist; so that even when he left theatre for cinema, he always made films for a social cause.

Cinema, to him, was a form of protest; and more than any other artist of his time, he used this medium to highlight the biggest contemporary issue in India – partition and its aftermath. As he once said: “[Cinema, to me,] is a means of expressing my anger at the sorrows and sufferings of my people. Being a Bengali from East Bengal, I have seen untold miseries inflicted on my people in the name of independence – which is fake and a sham. I have reacted violently to this – and I have tried to portray different aspects of this [in my films].”

He was, however, averse to the term “refugee problem”. In one of his interviews, he said, “I have tackled the refugee problem, as you have used the term, not as a ‘refugee’ problem. To me it was the division of a culture and I was shocked”. This shock would give birth to a trilogy on partition – Meghe Dhaka Tara (“The Cloud-capped Star”), 1960; Komal Gandhar (“E Flat”), 1961; and Subarnarekha (“The Golden Thread”), 1962. In them, he highlighted the insecurity and anxiety engendered by the homelessness of the refugees of Bengal; tried to convey how Partition struck at the roots of Bengali culture; and sought to express the nostalgia and yearning that many Bengalis felt for their pre-Partition way of life.

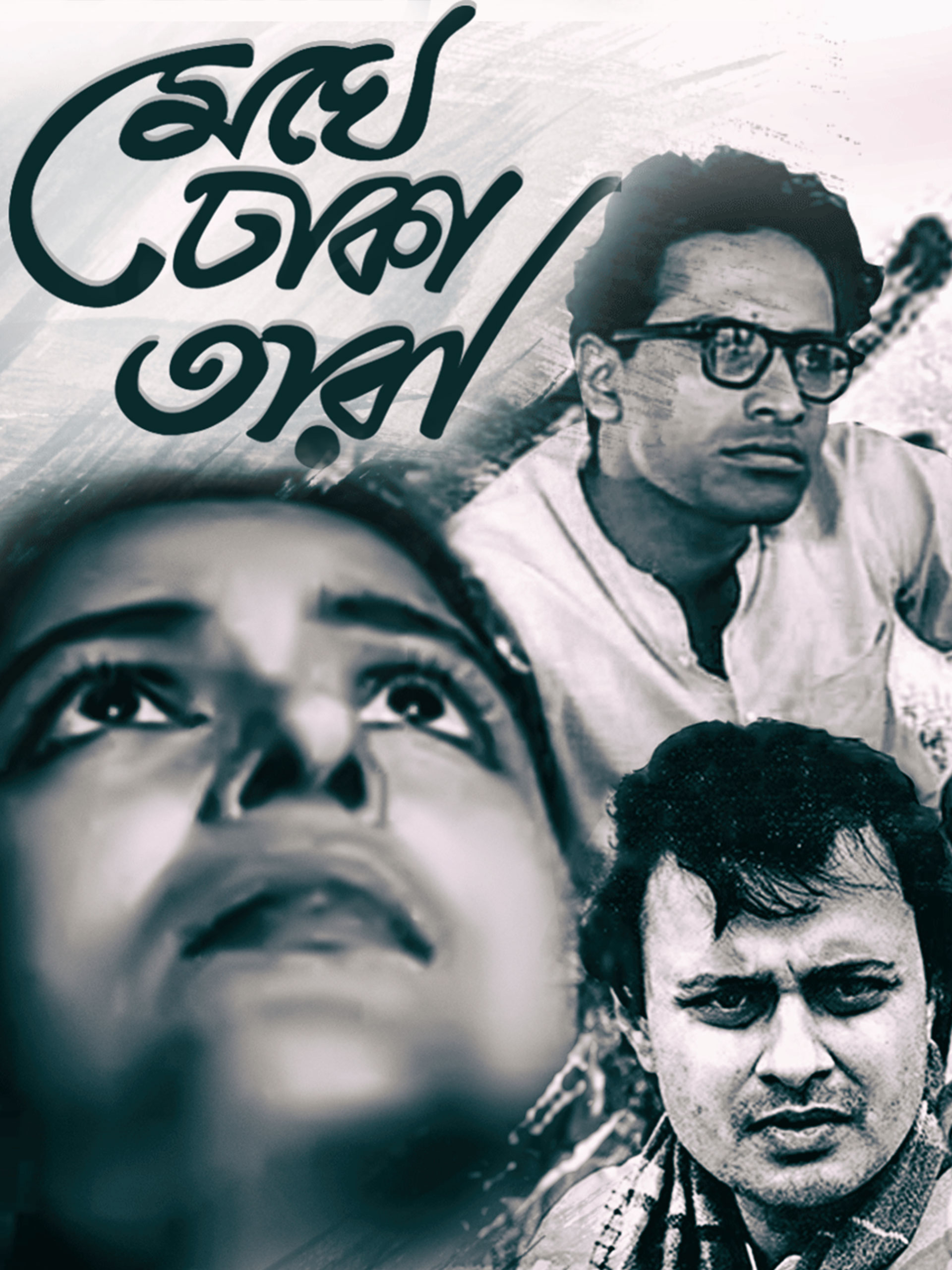

Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960)

Meghe Dhaka Tara (based on Shaktipada Rajguru’s Bengali novel of the same name) is one of Ghatak’s best-known films on this theme. It also has the distinction of being the only film by him that had been well received on its release.

A lot has been written on the mythic dimension of the narrative of Meghe Dhaka Tara and its many innovative technical aspects (especially in Ghatak’s use of sound). My aim, however, is not to analyze the aesthetic achievements of the film – but rather, to use it as a visual text to highlight the issue of women’s emancipation in post-partition West Bengal, especially vis-à-vis its relationship with employment. In doing so, I do not intend to reduce the immense richness and complexity of Ghatak’s art; but only to draw closer attention to a very interesting socio-historical aspect of the film.

Meghe Dhaka Tara centers round Nita (Supriya Chowdhury), a refugee girl in a colony in Calcutta, who struggles to maintain her impoverished family – at first, giving private tuitions to school children; and then, as the financial situation worsens at home, by working full-time in an office, giving up on her own post-graduate studies.

She is the exploited daughter, taken-for-granted sister, and betrayed lover in the film – and ends up being just a source of income for the family. She is the victim not just of Partition, but of familial pressures, and her life ends tragically fighting TB – though not before she cries out her desire to live to her brother in a hill sanatorium and admitting that she had wronged in accepting injustice, that she should have protested for her rights.

The partition connection in Meghe Dhaka Tara is not as obvious as for example, Komal Gandhar, where Ghatak talks about the Partition of 1947 directly, as something witnessed by his protagonists; but to a discerning viewer, the signs are all there – either incidentally or in the background.

At the very beginning of the film, the father (Bijon Bhattacharya) tells the mother of an impending ‘eviction order’ and the closing of the ‘school grant’ that were discussed in the last committee meeting that he attended; soon after, he is reminded by some colony boys that he has not given the colony subscription for three-months and that they would come to collect it next morning; throughout the film, at regular intervals, as part of the incidental noise of the soundtrack, colony school children can be heard naming tables in their makeshift open-air school – the kind that had sprung up like mushrooms in the hundreds of refugee colonies in Calcutta; the father complains to one of the colony boys about the collective insecurity of the refugees – (“Whom are we living under?” he asks, “Why can’t we sleep at night?”); the mother (Gita Dey) regrets, in an intimate moment with her elder daughter, that ten years of poverty and deprivation has made her a different person.

But the most important symbol of Partition in Meghe Dhaka Tara is Nita herself. She is the living embodiment of refugee life – the working woman.

Nita: the refugee working woman

Partition and its aftermath affected refugee women in two ways – it either victimized them or accorded them a new agency. But both turned out to be very complex, traumatic processes.

One of the central facts of the partition of 1947 was the sexual violence against women – and it was only appropriate that this aspect should be highlighted, once women became the proper subjects of partition narratives, in both history and fiction. As the seminal works by women historians focussing on the Punjab testify – the narrative of partition violence against women was not a simple one. It told the extraordinary sufferings that women went through at the time of partition – in some cases killed by their own families to prevent them from falling into the hands of the other community; in other cases, raped and abducted (remember Deepa Mehta’s 1947: Earth?), and then recovered or rejected by their original families; in yet others, settling for a new life with their abductors (remember Pinjar?) only to have their choices overturned by tribunals set up by agreement between the two new states of India and Pakistan.

But there was another important aspect of partition and a number of recent writers and historians have chosen to highlight that – of how partition enabled women; how some of them triumphed, despite their trauma. In the aftermath of partition, refugee women – both in Punjab and Bengal – faced the enormous challenge of rebuilding their lives from scratch. And, to be able to do so, they moved out of their domestic sphere and entered the public domain. For the first time, they joined the work force and became bread winners. For the first time, their education became linked with employment and not marriage.

There was another dimension to this issue as far as West Bengal was concerned. Some of the concerns of the refugee women actually evolved into a new women’s movement. There was already a women’s movement existent in Bengal by the 1940s, of which Chabi Basu, and later, Manikuntala Sen, have written memorably. The Communist Party of India (CPI) had created a women’s wing, MARS (Mahila Atma Raksha Samity), which was very active during the Bengal famine years. Then there was the Tebhaga Andolan, a peasant movement, once again spearheaded by women, who fought to retain 2/3rds of the agricultural produce for themselves. But after partition, this movement took a new turn and brought within its fold the destitute urban middle class as well.

This is a very interesting history in itself. But the point that needs to be remembered here is that, despite the women’s movement in Bengal, there still remained thousands of women who were neither activists nor members of any political party – but whose lives were transformed, nevertheless, by the whole process of forced migration and struggle for survival, like Nita in Ghatak’s film. And, just like the victims of partition, the stories of these women, who became bread-winners, were also not uniform or simple.

An important question in this respect was – though coming out of their narrow domestic sphere was a step towards emancipation for these refugee women, was this new-found agency/enablement really working in their favour? If we are to go by the testimony of Nita’s story, it was not. In many cases, it actually turned out to be yet another form of exploitation by a patriarchal society that now masqueraded as being ‘modern’.

As Ghatak’s film bears out, there were two aspects of this emancipation which were very disturbing. The first was that, the basic attitude of Indian society towards women remained the same – that of exploitation. Previously, they were exploited in one way, now in another. Only the form changed. In a crucial scene of Meghe Dhaka Tara, the father says: “In an earlier era, young Hindu girls were forced to marry dying old men and then burnt along with them [the custom of ‘Sati’]. We called them barbarous. And now, we educate our daughters, allow them to earn, and then suck them dry. Where’s the difference then?” In a later scene, towards the end of the film, when he comes to know of Nita’s illness, in a burst of impotent rage, he shouts: “I accuse…”, but when his son demands, “Whom?”, he replies uncertainly, “Nobody”. Needless to say, through this scene, Ghatak was actually implicating postcolonial society at large for Nita’s tragedy”.

The second intriguing aspect of women’s emancipation in post-partition West Bengal was that, though women were now employed, their essential role remained the same – that of nurturer. Previously, their nurturing duty was confined to the domestic space. Now, that space got expanded, but their roles did not change. Women and their work were still thought of solely in terms of home and the family; and their employment not valued for its own sake. Nita, in Ghatak’s film, is born on Jagaddhatri Day. Jagaddhatri is another form of the goddess Durga, and the audience is left in no doubt of her nurturing role.

In the film, at the height of her relentless struggle against poverty, Nita emphatically declares she does not want to be a mannequin, when she is told separately by her brother and her fiancé – both of whom are financially dependant on her and feel guilty about it – that she has taken on tremendous pressure on herself and she deserves a more relaxed life. She replies that she madly loves her family and has willingly taken up a job to look after her aged parents, take care of her younger brother and sister, and support her elder brother and fiancé. But she does not value it for its own sake. She is basically waiting for two things to happen – for her classical singer elder brother (Shankar/ Anil Chatterjee) to become a performing artist and her lover (Sanat/ Niranjan Ray) to complete his Ph.D. Once that happens, she says, once the men in her life start earning, all her struggles will come to an end and she would happily give up her work. Her attitude to being the breadwinner is thus of a person who is only filling in for the time being. In this, she is representative of her times; as a lot of refugee women in colonies did indeed give up their jobs once their families became financially solvent.

Nita’s fate is different, though. What makes her eventual tragedy particularly poignant is that she faces multiple betrayals from those closest to her, and by life itself. Her hopes for the future are dashed to the ground when she loses Sanat to her younger sister, Gita (an act of treachery that her mother condones, but her father and Shankar protest); and then loses her life fighting tuberculosis. Shankar, however, does not fail her. As an eminent film critic has pointed out, Nita’s most intimate bond is with Shankar, not Sanat; and in this, it is not unlike most of Ghatak’s films “… from the 1950s and ’60s [which] show a compulsive engagement with the brother-sister relationship…. [where] brothers and sisters… appear as exemplars of the pure couple.”

Nita and Shankar’s bond remains intact throughout the film, though it takes an ironic turn after she is diagnosed with TB. True to his promise to his sister, Shankar not only becomes the successful and acclaimed classical singer that he always wanted to be, but with his huge earnings, brings in affluence for the impoverished household as well. His sister’s unshakeable faith in his talent is thus vindicated, but she is herself unable to enjoy its benefits. Shankar also keeps another promise. He takes her to the hills – though, ironically, the fulfilment of this wish of hers happens not for a vacation, but to spend her last days in a hill sanatorium. She is now redundant in the family that she had worked so hard to maintain, sacrificing her own dreams and desires. But in an unforgettable cinematic moment of defiance, she cries out her desire, her will to live – “Dada ami bachte chai… dada, ami bachbo…” – her heart-rending cry reverberating in the hills.

It is an established fact that refugee women played a very important role in the steady emergence of women in the public domain in West Bengal since 1947. Starting with women like Nita, who looked upon their new roles as tentative and temporary, there was a gradual shift in attitude in later years, when lower/ middle-class women confidently embraced their new working avatars (whatever the conflicts it involved in the domestic sphere) and became equal partners/comrades of men in life’s struggle. Arati in Satyajit Ray’s film, Mahanagar (“The Big City”) is one such woman. But there is no doubt that it is the Nitas who paved the way for the Aratis in West Bengal. And it is to Ritwik Ghatak’s credit that he could bring out all the complexities of Nita’s historical time and milieu in Meghe Dhaka Tara, and thereby immortalize the Bengali refugee woman on celluloid.