2 States (Just Released)

Love marriages around the world are simple:

Boy loves girl. Girl loves boy. They get married.

In India, there are a few more steps:

Boy loves girl. Girl loves boy.

Girl’s family has to love boy. Boy’s family has to love girl.

Girl’s family has to love boy’s family. Boy’s family has to love girl’s family.

Girl and boy still love each other. They get married.

Thus goes the blurb of the book 2 States by Chetan Bhagat. The trailer of the film based on it also cashes in on this catch line and rightfully so, as the story is a humorous take on inter-community marriages in India today. A Punjabi boy and a Tamil Brahmin girl – Krish Malhotra and Ananya Swaminathan – meet and fall in love in college, want to marry, but face parental opposition. They overcome this obstacle bravely and their love story becomes a love marriage when their Punjabi and Tamilian parents finally give their consent. In an interview, Chetan Bhagat had once said that true national integration can only happen when there are more inter-community marriages in India. I don’t think Karan Johar got interested in producing 2 States because he wanted to promote national integration; rather, it fitted in very well with one of Bollywood’s time-tested formulas – parental opposition to love.

Though 2 States is based on an autobiographical story (Bhagat’s own tryst with love and marriage), in the context of Bollywood history, the film is actually a cross between Ek Duje Ke Liye (1980) & Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (or DDLJ, as it later came to be known, 1995). Ek Duje, starring Kamal Hassan & Roti Agnihotri, was a Romeo-Juliet story, something that Bollywood never tires of, with every generation having its own version, usually with newcomers (there was Qayamat se Qayamat tak or QSQT, with Aamir Khan & Juhi Chawla in 1989; and the very recent Ram Leela,with Ranvir Singh & Deepika Padukone in 2013). What 2 States has in common with Ek Duje is the inter-community romance & it kind of marries that to the ‘boy winning over his reluctant in-laws’ theme of DDLJ.

The first reviews are already out. To give you a sample of the two ends of the pole, while NDTV Movies dismisses the film by saying “The unabashed shallowness of a Chetan Bhagat book meets the inane glitter of a Karan Johar-Sajid Nadiadwala production in 2 States”;India TV praises it as “… a classic example of the problems evoking prior the marital life of a couple from two different cultures. Abhishek Verman deserves applause for understanding the usual yet non-described feelings and mindsets of two different communities and narrating it with ease.” They (as well as other reviews) however agree on the competency of the actors – both the lead pair and their parents (played by Revathi and Shiv Subramaniam on the one hand & Amrita Singh and Ronit Roy on the other).

I personally think that despite its flaws, the film may score in two respects: with more and more Indians seeking higher education and jobs outside their home states, inter-community romance and marriages are a reality in India in a way they were not till a decade ago; it willtouch a chord with such couples (however sedate their own romance may have been). Also, for many young viewers, this film would be wish-fulfilment of the highest order: Krish and Ananya study at IIM-A, find an attractive partner, secure high-paying jobs immediately after graduation and (after the parents are appeased), most likely, get to live the life of their dreams. This is what every college kid aspires to these days in an India that is incessantly upwardly mobile.

Chetan Bhagat & Bollywood

2 States has understandably high expectations from the audience – not just because it follows soon on the heels of the recent successes (Highway & Gunday) of its lead pair Alia Bhatt and Arjun Kapoor, and is produced by Karan Johar whose films habitually cross the 100-crore mark, but perhaps even more for the fact that it is a Chetan Bhagat story. 2 States is the third Hindi film to be based on a novel by Chetan Bhagat in just 6 years (after Hello in 2008 & the blockbuster 3 Idiots in 2009), and that speaks volumes about Bhagat’s popularity with India’s young. By now everybody knows that the New York Times had touted him to be ‘the biggest selling English-language novelist in India’s history’. Amish Patel might soon change that statistic, but for the time being, Bhagat is still the king of numbers and the current darling of Bollywood to boot!

He has also given a new boost to Bollywood’s sporadic affair with Indian-English fiction. Bollywood has had a lifelong affair with Bengali literature (even apart from Devdas & Parineeta). Umpteen Hindi films have been based on Bengali novels and short stories, just as many have been from Hindi and Urdu fiction, but very few films in Bollywood’s 100-year history have been inspired by or based on Indian-English fiction. That is probably because this literature was not taken seriously in India in general for a very long time. The immediate predecessor of 2 States in Bollywood is of course Raj Kumar Hirani’s 3 Idiots (2009), but its lineage actually dates back to the 1960s and 70s – to Vijay Anand’s Guide (1965) & Shyam Benegal’s Junoon (1978).

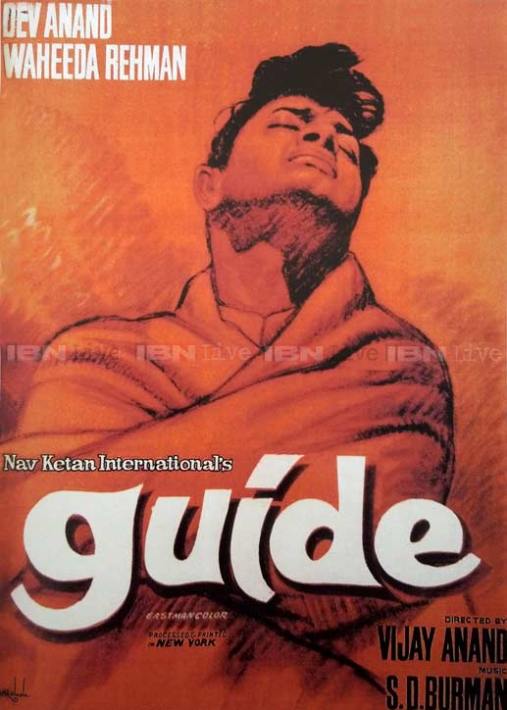

Guide (1965)

Vijay Anand’s debut film as a director is one of Bollywood’s greatest hits ever. Based on R.K. Narayan’s Sahitya Academy winning novel, it came to Nav Ketan International (the production company of the famous Anand brothers) in a circuitous way. It was originally supposed to be a joint Indo-American production with Dev Anand in the lead, but that fell through; Dev Anand, however, did not give up on the film and later produced it, with himself and Waheeda Rehman in the lead roles.

It had a very unusual story: set in Narayan’s imaginative world of Malgudi, it is about the transformation of a tourist guide, Raju, into a spiritual leader – albeit accidentally. The catalyst is Rosie. She is a classical dancer, daughter of a devdasi, who married an archaeologist much older than herself (Marco) to gain respectability. The couple come to Malgudi owing to Marco’s research interest in its Caves, but their already unhappy marriage falls apart when Marco cheats on Rosie with a tribal girl. Rosie attempts suicide but is saved by Raju, who by then had befriended her. They fall in love and Rosie leaves Marco and takes shelter in Raju’s house. His mother is unable to accept this relationship and leaves the house; they are also socially ostracized thereafter, but they take it in their stride and jointly invest in a new ambition – Rosie’s dancing career. Inspired by Raju’s encouragement of her art (which she had been forced to give up against her will after her marriage), Rosie now devotes herself to dancing. Raju becomes her manager, and after Rosie’s initial success, they move out of Raju’s humble abode into a huge mansion of their own. But their personal relationship degenerates – Raju lives off Rosie and she, too full of her own career, drifts further away from him. Matters come to a head when Marco attempts to come back in her life, and Raju, insecure and afraid of losing Rosie, forges her signature to pre-empt further contact between them. He is convicted of forgery and sentenced to two years of prison, but released earlier because of his good conduct. Reluctant to return to Malgudi, he finds himself in the company of wandering ascetics in a small village where he is mistaken to be a sadhu. He takes to this as an actor and then becomes the role. Leaving his past behind him, he now participates in the life of the village as its spiritual guide, so that when it is affected by drought, the villagers naturally assume that he will fast for them. Fast to end the drought and bring rains. He is now caught in a dilemma of his own making and undertakes the fast.

The film diverged from the book in many ways. The end was open-ended in the novel, whereas in the film, Raju dies in the end. More important, perhaps, is the difference in the characterization of Rosie: Rosie leaves Marco in the novel because she herself is in love with Raju and not because her husband is unfaithful to her. That was too much for a Hindi film in the 1960s, where women had no choice but to be pativratas (devoted to their husbands). Whereas the initial romance of Raju and Rosy and its later wearing away has been dramatized gloriously in the film (both through dialogue and unforgettable songs), the inconsistencies and complexity of Rosie’s character are bulldozed over to make way for a neater narrative in line with audience expectations of that era.

R.K. Narayan was very disappointed with the Hindi film and devoted an entire chapter in his autobiography (My Days) on it. Indeed, it is perhaps better to enjoy the film on its own, as just a Dev Anand movie! Anand was great in the title role, as was Waheeda as the classical dancer. And of course what worked to the biggest advantage of the film was the dancer character – for here was a story that lent itself most naturally to the song-and-dance routines of mainstream Bollywood! Little wonder that it remains popular to this day.

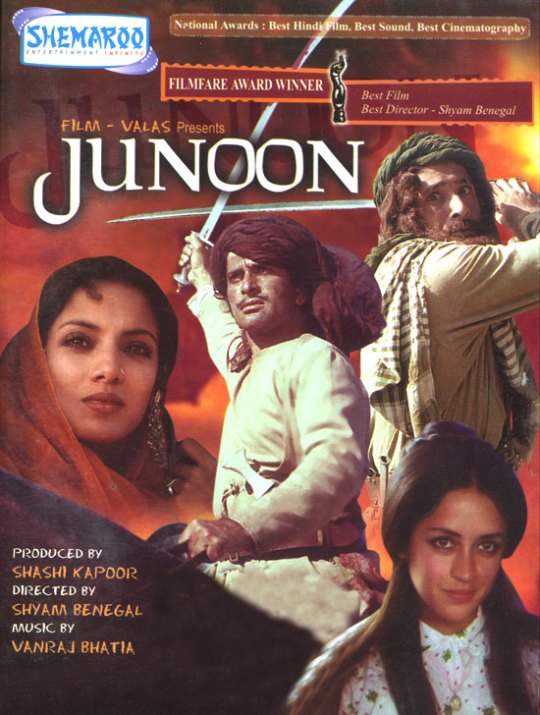

Junoon(1978)

More than a decade after Guide came Junoon. The backdrop of the film, based on Ruskin Bond’s English novella A Flight of Pigeons, is the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. But the story is about a married Muslim landlord’s (Javed Khan/ Shashi Kapoor) irresistible attraction for an English girl (Ruth/ debutant Nafisa Ali), whom he locks up along with her mother in his zenana (to the impotent outrage of his wife, Firdaus/ Shabana Azmi).The beautiful young girl is terrorized and has endless nightmares of being violated by this strange man whose passion for her she cannot fathom. The mother (Miriam/ Jennifer Kendal) is, however, incipiently grateful for the protection that this man provides in the rising tensions of the progressing mutiny and the violent anti-British sentiments that it unleashes, though she stubbornly refuses his marriage proposal to her daughter. The tide turns, the British ruthlessly suppress the revolt and the English women need not fear anymore. But by this time, the zenana already bonds the women in a kind of unarticulated, undefined sisterhood – and the English girl, by slow degrees, softens towards her captor. Her final moment of release is also the moment of love – she realizes that she does not want to escape from him any more. But by then, it is too late… and an erotic, perplexed, last gaze is all the consummation they have.

Junoon was a very interesting collaboration between Shyam Benegal and Shashi Kapoor. Both started a new phase in their careers with it. By 1978, Benegal had already established himself as the pioneer of parallel cinema in India with films like Ankur (1973), Nishant (1975), Manthan (1976) and Bhoomika (1977); & Shashi Kapoor had proved his mettle beyond Bollywood by being part of several Merchant-Ivory Productions – The Householder (1963), Shakespeare Wallah (1965), Bombay Talkie (1970) – all of which were English films with Indian content. Their collaboration thus created a unique synergy: Benegal brought the full might of the parallel cinema brigade (Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Kulbhushan Kharbanda) to bear upon this commercial venture; while Kapoor’s involvement ensured that the film was an elegant literary adaptation, which was a hallmark of Merchant-Ivory productions. Benegal and Kapoor were to come together again in Kalyug (1981); and Kapoor went on to produce some other off-beat films in the 80s – Vijeta (1982), Utsav (1984) & the cult English film, 36 Chowringhee Lane (also 1981) by Aparna Sen. But none of them did a Hindi film based on an Indian-English story again. Nor did anyone else for a long time.

Guide & Junoon thus represent two phases of Bollywood’s affair with Indian-English fiction, separated by more than a decade – one was a Hollywood production gone wrong; and the other was an Indian production with a Raj story, but inspired to some measure by the Merchant-Ivory brand. The time was now ripe for a completely home-grown, mainstream Hindi film by a big banner inspired by an Indian-English story. It was 30 years before that could be accomplished with 3 Idiots in 2009!

In between, there were several English films adapted from Indian-English stories – Hollywood ventures by a diasporic Indian & independent films by non-Bollywood filmmakers. I’m referring here first to Deepa Mehta’s 1947: Earth (1998) & Midnight’s Children (2012); and next to Shonali Bose’s Amu (2005) & Aparna Sen’s The Japanese Wife (2010).

The 30-year gap is a long one; such a gap doesn’t help in the development of a tradition in filmmaking (and it would not in any other art form as well). But Indian-English literature was kept alive in the collective imaginary of India’s cinematic audience in the intervening time with two exceptionally successful TV Series in the 1980s – Shamkar Nag’s Malgudi Days (1986), based on R.K. Narayan’s short stories; and Shyam Benegal’s Bharat Ek Khoj (1988), based on Jawaharlal Nehru’s historical narrative, The Discovery of India.