Aparna Sen & the many hues of Love

“There are many kinds of love, Mini… you are thinking of only one.”

Author Chintan Nair says this to actor Mrinalini in Aparna Sen’s film Iti Mrinalini (An Unfinished Letter). The young Mrinalini (played by Konkona Sen Sharma) bonds with Chintan (Kaushik Sen) at a time when her relationship with her lover (Siddharth, played by Rajat Kapoor) is in turmoil. Sid is a married man with two children who refuses to acknowledge his relationship with Mrinalini in public. They marry in secret and have a love-child; but she is brought up by Mrinalini’s brother and his wife in Canada, away from prying eyes, knowing her mother to be her aunt. At one point, Mini loses even this sham of a family – her daughter dies in a plain crash and she leaves Sid. It is then, when she is overwhelmed with a sense of futility, that Chintan reminds her that romantic love culminating in a socially recognized marriage is not the only kind of love in the world. There are other kinds… like the kind he has for her. He leaves that unsaid, but Mini understands. They are two sensitive souls who initially bond over literature, and eventually become the closest of friends, sharing their lives and empathizing with each other’s pain regarding a child (Mini’s child cannot be hers, while Chintan’s wife, owing to an accident that leaves her crippled, cannot bear one). Over time, their friendship deepens into love, an unspoken love that lasts a lifetime, and at a crucial moment, actually helps Mini overcome a suicide attempt. Her suicide note (referred to in the title), with which the film begins, thus remains unfinished.

Sen’s ouevre

Iti Mrinalini is Sen’s 9th film in her 30-year career as filmmaker, and Chintan’s timely reminder to Mrinalini happens to be one of the most abiding themes of her oeuvre – namely, the many hues of love, or (if I may put it so) meaningful relationships beyond marriage. She is not the only director to have dealt with this theme, but she is certainly the only one to have done so time and again over three decades. She is different in other ways, too – little wonder, as she had in fact set out to be different when she turned to direction.

Sen, as is well known, was an actor before being a director. She had a dream debut in Satyajit Ray’s Teen Kanya [Three Daughters] in 1961 while still in school, but took up acting professionally only in 1965. In the next fifteen years, she established herself as one of the foremost stars of commercial Bengali cinema, working with the best talents of the industry. But at the height of her success, she changed tracks. Her transition from acting to direction was born of a deep dissatisfaction with the kind of films she mostly worked in. There is a wonderful anecdote about this phase in her life. She had always had a flair for writing, and once, while composing a story between shoots, she ended a scene writing ‘dissolve’. She realized then that films were too deep in her blood to let go and she embarked on a new journey on the road not taken before – direction; encouraged and supported in this brave decision by her ‘Manik kaka’ (Ray). Her story about an Anglo-Indian school teacher became the screenplay of her first directorial venture.

It was a first not only in her career but also in the history of Bengali cinema. Bengali directors had made Hindi films before and Bengali actors had acted in English films but no Bengali had made an English feature before her. This was a Calcutta story in English. It announced the arrival of not only a new talent but a new sensibility on celluloid, very different from the Bengali greats (Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak) Sen greatly admired and (two of whom she) had herself worked with.

Aparna Sen’s stories are mostly set in Calcutta (like Ray & Mrinal Sen & many others), but they are predominantly women-centric. Her protagonists also happen to be essentially lonely/marginal characters – the ageing Anglo-Indian teacher, Miss Donam, who finds temporary companionship with a pair of lovers (36 Chowringhee Lane, 1981); the housewife Paroma, drawn out of her doll’s house by a liberating affair, but with tragic consequences (Paroma, 1984); the sorrowful bonding of Shonoka and Paromita, mothers of autistic children (Paromitar Ek Din, ‘House of Memories’, 2000); the schizophrenic Mithi who lives in a delusional world of her own, forever searching an address that does not exist (15 Park Avenue, 2005); the actor Mrinalini with her unusual loves and relationships (Iti Mrinalini, ‘An Unfinished Letter…’, 2011).

This blog-post, however, focuses not on the loneliness of the protagonists, but their attempts at connection. They all have romantic longings which are fulfilled in strange ways – through meaningful relationships beyond marriage. These relationships are all distinct from each other, but are invariably an enriching experience for the woman (however sad or tragic) – as in each case, they help the woman to either discover or understand something about herself that she did not know before, and ultimately contributes to the evolution of her self. They are all the wiser – and in one case happier – for the unusual love in their lives.

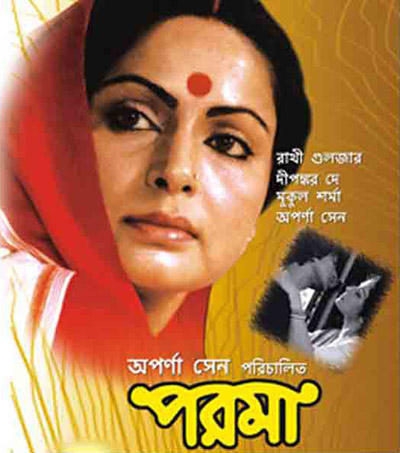

I. The adulterous affair: Paroma (1981)

Adultery is always an escape, a getaway car from a stifling marriage. All the famous adulterous woman in literature – Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, Lady Chatterley – have this factor in common. As do their real life counterparts over centuries. Sen’s Paroma is typical in this: it is about the adulterous affair of a lonely woman. Paroma (Rakhee Gulzar) is the quintessential housewife, without whom her home and its members (husband, three children, mother-in-law) are dysfunctional. She is everything that she is supposed to be – loving mother, caring wife, dutiful daughter-in-law. She has no time to visit her own mother, though, and she rarely meets her friends.

Enter Rahul (Rahul Sharma), a photo-journalist who comes to cover Durga Puja in her family home in Calcutta, but ends up photographing Paroma more than the idol. He is fascinated by her beauty and, a year after, is eager to make her his proper ‘subject’ as ‘the Indian housewife’. She refuses promptly, but her family insists that she relent. It is through these photo sessions – at first reluctant, hesitant and then comfortable – that Rahul and Paroma come close. He is keen to know his subject: all that goes to make up her ordinary day, her interests, her maiden days. He not only gives her the kind of attention that she has never known, but also helps her reconnect with herself, her past, and the things she loves – her sitar (whose rings had sat forlorn with long disuse in her dressing-table drawer), poetry, her family home with its terrace. He even introduces her to her own city, which she now sees with new eyes. She is drawn to him inexorably but resists herself. Ironically, it is in a moment of farewell that she gives in to him; from then on, with Rahul’s stay in Calcutta extended, their affair follows a predictable pattern – secret meetings, their growing indifference towards others and the world around them even as they discover more of each other, the acute consciousness that they have very little time together, the looming fear of separation and anxiety for an uncertain future. There are shades of Anna Karenina in the film – not only in the much younger lover (Rahul is the friend of Paroma’s nephew), but also in the social ostracism that follows the revelation of the affair, and the furious husband who does not allow the son near his mother. The added dimension here is that of the college-going daughter, who senses the change in Paroma during her affair and resents it fiercely.

I remember an anecdote that a colleague of mine had shared with me once. She told me that when Paroma released, she was studying in college and remembered that a lot of her friends did not want their mothers to see the film! That is the kind of impact that this defining film by Sen had in Kolkata. I myself was too small to see the film then (my parents saw it on their anniversary, I remember); saw it much later and greatly admired Sen’s utter honesty and realistic depiction of an adulterous affair that could only have ended in disaster.

II. A Second chance: Paromitar Ek Din (1999)

The literal translation of the title would be, ‘One day in the life of Paromita’. And the film is exactly that. In the course of a day, a whole life unfolds before us. (I am not sure whether Sen was inspired by Joyce’s Ulysses for the idea of her film, but even if she was, her audience thankfully did not have to sit with a reference book to understand it!) Paromita (Rituparna Sengupta) attends the ‘sraddh’ ceremony of her former mother-in-law in the house where she was once a wife, and then heads back to her office escorted by her present husband. Throughout the day she reminiscences, and we are let into her life through these memories, in a series of flashbacks. Married to a moron of a husband, she cannot connect with him, but she bonds with the women of the family – his mother Shonoka (Aparna Sen) and sister Khuku (Sohini Sengupta). Both Khuku and Paromita’s own son, Bablu, are autistic, and it is this that brings the three women together in a shared solidarity of pain.

A new phase in her life begins when her son starts going to school, and it is he who brings her close to the filmmaker who would change her life. When they meet, Rajeev Shrivastav (Rajesh Sharma) had been shooting a documentary film on mentally challenged children for a while, and hence could empathize with Paromita’s pain. He gives her strength and courage, not only to value her child, but also herself. He encourages her to start working and gives her a new confidence; so that even after she tragically loses her son – the centre of her universe – she still finds the strength to start life anew. Life gives her a second chance at love – she marries Rajeev, this time she is genuinely happy, and at the end of the film, she is expecting his child.

Paromita in this film does what Paroma could not – she not only walks out of a stifling/ meaningless marriage, but also has the courage to articulate her reasons for doing so with calm confidence to her mother-in-law. That she is able to do it is not only because the relationship she shares with Shonoka (which is at the heart of the film) is not that of the stereotypical saas-bahu, but also because of her moral conviction of the ‘rightness’ of her choice. Paroma (at the end of the film) had shocked her family by saying she did not feel “guilty” for her affair; Paromita goes a step further – she demands a second chance at love, at happiness, as something she rightfully deserves.

III. Romancing the Stanger: Mr. & Mrs. Iyer (2003)

This is a romantic story that unfolds against a communal backdrop. Meenakshi Iyer (Konkona Sensharma), a young South Indian mother undertakes a long bus journey with a baby. Communal riots flare up in the route of the bus and it is forced to halt. Mrs. Iyers’ travelling companion is Raja Choudhury (Rahul Bose), a wildlife photographer who is wonderfully patient with her crying baby. She is grateful to him for putting up with Santhanam (her son) and is just warming up to his presence when he announces that he is a Muslim and hence will leave the bus, as communal rioters are hounding out Muslims and his presence might endanger others. She is shocked; she had taken him to be a Hindu – Raja Choudhury could easily have been a Hindu name – but she saves him nevertheless when the rioters do come to search the bus. When they ask for names, she answers them before Raja can: “Mr. & Mrs. Iyer. Subramaniam Iyer – and that is our son, Santhanam”, she says. Santhanam was already on Raja’s lap and the latter had no outward signs of being a Muslim. So, the bloodthirsty mob believed them to be a couple; as did the rest of the passengers, as Raja had been sitting with Meenakshi and her son all the while.

The journey now takes an altogether different turn. There is a curfew, and unable to find any other accommodation, they are forced to take shelter in an abandoned forest bungalow, aided in this by a kind police officer.They now have to perforce act out the couple – she is furious at this turn of events; he is uncomfortable, but most of all shocked by her prejudices and communal bias. But they had to ride out the storm together and it is Sandy (rechristened by Raja) who is of help here, his presence easing out their tension despite themselves. They are even granted moments of intimacy that Meenakshi has rarely had with her husband (who perpetually travels, as we come to know) – a photo-session in the woods on a sunny morning, sharing childhood memories on the balcony in the silence of the evening. They once venture out and a bunch of young girls (from the bus) ask them how they had met: Raja spins an instant yarn of their meeting and marriage and honeymoon, Meenakshi joins after the initial surprise, drawn in by his romantic conjuring. Indeed, what he says is the stuff romantic dreams are made of.

Meenakshi’s prejudiced dislike of Raja’s Muslim identity had already thawed by degrees, but they come really close after they share a terrible moment together – the witnessing of a communal murder from their bungalow window. She breaks down, he comforts her, and they end up spending the night in the same room, she on the bed and Raja on the floor besides her holding her hand that she didn’t let go. The communal situation in the area improves soon after, and the helpful police officer drives them to the nearest train station that would take them to Kolkata, their final destination. That last bit of train journey is the most poignant part of the film – all too conscious of their imminent separation just when they had connected, they now indulge in a playful romantic fantasy. The closest they come to physical contact is a kiss… that however remains unconsummated, because of an intruding passenger.

It all happens in only a few days and yet, their bonding seems gradual. The romance in the film develops at a plausible pace; nothing is forced for the sake of a romantic story. The irony is that, though ‘Mr. & Mrs. Iyer’ are a make-believe couple for a few days, by the time they undertake the train journey, that make-belief had begun to seem real to them. They were no more strangers, and they were parting now because they had to. (I am reminded of A Roman Holiday here). When the train arrives at Howrah, the real Mr. Iyer, Meenakshi’s husband, is all gratefulness to Raja for safely bringing his wife and son back to him. It is time to part and Meenakshi says, “Goodbye Mr. Iyer”.

The film got many awards – in India, Locarno, Hawaii, Philadelphia. Apart from the usual cinematic categories, one of the special awards that it received was ‘The Nargis Dutt Award for Best Feature Film on National Integration’ in India. In a post-Godhra India, the award certainly had its significance; for me, however, its value lies not in the national integration part but the romance. I think even if the story had a different backdrop, the beauty of the romance would still stand.

I actually find it interesting from a very different angle. Meeting/Falling in love with a stranger is a common fantasy of women (and of men too, I am sure) – but in Mr & Mrs Iyer, Sen gives it an altogether different appeal by making the child an integral part of the romantic experience. If anything, it is he who makes the romance possible, and adds to it.

IV. Epistolary Romance: The Japanese Wife (2008)

When was the last time you wrote a letter? Wrote, not typed. Wrote with pen on paper and sent it by post, eagerly awaiting the arrival of its reply in your letter-box? Let me guess – two decades ago? (That will be those of you who are much more than two decades old!) In the internet-driven world that we all inhabit, the charm of the old-fashioned letter has been sadly lost, and with it, that ultimate romantic thing – the love-letter. Epistolary romance was however partially retrieved for the English viewer (and later reader) with The Japanese Wife. The film is a beautiful though impossible tale of love – and marriage – between two people who never meet! This is the first time that Sen used someone else’s story for her film (though she wrote the screenplay herself) – the title story of Kunal Basu’s collection of English shorts. In an interview I had taken of Basu in August 2008, he had said that, as far as the essence of the story was concerned, Sen and he “were on the same page”. Indeed, the film was a meeting of two beautiful minds; and it came as no surprise to me that Sen should be fascinated by Basu’s story, as it is a celebration of love in a different vein.

Snehamoy (Rahul Bose), a school teacher in the Sunderbans writes to Miyage (Chigusa Takaku), a Japanese girl. They become pen-friends, fall in love and even marry over letters. To some extent, their life is the stuff that long distance relationships/ marriages are made of (albeit that of non-affluent couples, who cannot fly to each other nor have vacations together). But they do share their daily lives: he tells her of his relationship with the Matla, the river that took his parents away but was also his closest confidante; she writes to him about her mother’s prolonged illness and death; knowing that he flies kites, she sends him the most beautifully decorated Japanese ones, each with a distinct character; when she falls sick, he takes care of her in his own way, consulting doctors and sending her medicine. He almost loses her at one point, but she miraculously survives; yet, in the crowning irony of the story, it is he who dies, taken suddenly by the pneumonia that is common in the Sunderbans. She finally arrives at his home – after he dies, clad in the white of a Hindu widow. And the person who welcomes her is Sandhya (Raima Sen), the other woman in her husband’s life!

There are actually two romances in this most unusual of tales: apart from the epistolary romance of Snehamoy with Miyage, there is his wordless companionship with Sandhya – the girl originally chosen by his aunt (Moushumi Chatterjee) to be his bride, who marries another because of his rejection, is widowed with a small son, and on being forced to seek refuge away from her in-laws is voluntarily given shelter by Snehamoy’s aunt (who happened to be her mother’s best friend). She and her son become a palpable presence in the house, Snehamoy bonds with the boy, and they practically function as a family – so that Snehamoy now leads a strange double-life: enacting (to quote Basu), “marriage without domesticity [with Miyage] and domesticity without marriage [with Sandhya].” One relationship of his is thus defined by words, and the other by its absence – each teaching Snehamoy the possibilities and limits of human communication.

In an interview Aparna Sen had said that the opportunity for wonderful visuals was also one of the reasons that attracted her as a filmmaker to Kunal Basu’s story – and indeed the film, shot on location in the Sunderbans, is replete with scenes that are sheer visual poetry. But at no point are the visuals allowed to ride over the human story of love and compassion between three individuals.

V. Unconditional Love: Iti Mrinalini (An Unfinished Letter…, 2012)

I had started this post by quoting from Iti Mrinalini. Chintan’s consolation to a bereaved Mini about the many kinds of love comes as a revelation to her. In one stroke, with a single line, the insightful writer imbues meaning into the life of the actor by making her realize that the most important relationship in her life (with a director) had had its own value, even if it was not what she wanted it to be. “Why do you think all love must end in marriage?”, he had reasoned with her. “How many happy love relationships have you seen… in life, in literature? …. You wanted to have a home with Sid. Domestic Love. He couldn’t give you that. He was weak. But that doesn’t mean that he has never ever loved you. He had probably, in his own flawed way… There is another kind of love, too… the love where there is no expectation. Love that frees you.”

It is the recollection of this bit of conversation with Chintan that actually stalls Mrinalini’s suicide attempt (the elderly Mrinalini played by Aparna Sen herself). She is heartbroken when her much younger lover, Imtiaz (a director, once again), moves on in life with a wannabe star, and incapable of dealing with her loneliness anymore, she decides to end her life. But not before writing a suicide note. The hallmark of a good actor is “timing”, she writes, adding: on the stage that was her life, “The entry was not in my hands, but the exit is. In this uncertain life, let me at least retain this right.” Her suicide note is punctuated with memories – with her life unfolding to us on a single night, just as Paromita’s had over a day. And at the end of it, what saves her is her remembrance of the one love in her life where there was no expectation; the love that freed her as an individual, and had quietly remained a steady part of her life. She looks fondly at the photograph of the ageing Chintan on her desk and his last text message to her, deposits back the fistful sleeping pills in their container, and goes out for a morning walk with her dog Begum – smiling with a renewed faith in life. (That it ends tragically, nonetheless, in a most ironic twist of events, is a different matter).

Chintan in Iti Mrinalini is an author, and hence, understandably, thoughtful and wise, capable of showing Mrinalini what she could not see herself. But even the other men to whom the women of the above films get attracted are no ordinary mortals. Rahul (in Paroma), Rajeev (in Paromitar Ek Din) and Raja (in Mr & Mrs Iyer) are all photographers, exposed to and also devoted to exploring other worlds than that of everyday domesticity – and their open-mindedness is, as we see, brought to bear upon their relationship with the women. That, in fact, is what changes them – as the women get a glimpse of a wider world than the one they are forced to inhabit.

The Japanese Wife is an exception in this group – not only because it has a male protagonist, but also because all the three characters in the triangular relationship explored in the film lead humdrum lives. That however does not stand in the way of their sharing a unique bond.

‘Unique’ is also how I would describe Aparna Sen as a filmmaker. She has broken ground in Indian Cinema in many ways – one of which is her consistent exploration of the many hues of love. In doing so, she has redefined ‘romance’ in Indian films.