Suman Ghosh's ‘Puratawn’is essentially a loving and languid exploration of decay – both in living beings and the lived environment. Whether it is the gnarled roots of an ancient tree, the twisted veins visible on the skin of an octogenarian woman, or the crumbling bricks of an old mansion, we are invited to witness and acknowledge the continuity of life within decay; of the workings of slow time. The onset of dementia in a mother’s life - and how it’s dealt with - is only one strand in this larger narrative.

His last aspect may invite comparison with several recent films: Atanu Ghosh's ‘Mayurakshi’ (2017, with Soumitra and Prasenjit) & Pushan Kripalini's ‘Gold Fish’ (2022, with Deepti Naval and Kalki Koechlin) among them. The challenges of care giving and the moral dilemma of the only child – a son in one and a daughter in another (the latter also having a complicated personal relationship with the parent) – in confronting/negotiating with it are the central preoccupations in those films, as is the altered nature of the filial relationship itself. But ‘Puratawn’ is conceived in a different vein: while care giving is a concern, it is more taken up with indulging the mind-space of the delusional patient, who is still fully functional and whose physical autonomy has not been compromised yet. In fact, she is very much the mistress of the house and lives a perfectly normal life in terms of a quotidian routine. Only that, very often, she lives in the past – or rather, she lives out her past in her present: packing a tiffin-box for her middle-aged daughter, imagining her to be the little schoolgirl she once was; talking to her dead husband, the young householder who sat across her at the dining table; or seeing policemen chase her Naxal brother-in-law to his “encounter”.

She lives alone – sans any blood-family, i.e. – in the loving care of a domestic help who has been with her since she was a child, with periodic visits to a doctor who happens to be her daughter’s bestie. These women fill in the daughter, Ritika, played by Rituparna Sengupta, a partner in a consulting firm, with the changed reality of her mother’s life when she comes to celebrate her 80th along with her ex-husband.

Both Brishti Roy and Ekavali Khanna are memorable in their cameos as the help and the doctor, respectively; but it’s Indraneil Sengupta as the son-in-law, Rajeev, a wildlife photographer, who stands out in the supporting cast. He brings a quiet assurance to his character – even in turmoil – which is what harmonizes all the conflicting strains in the old house in Konnagar, inhabited by choice by his “auntie”. He doesn’t call her “Ma”, but it is he who is really tuned into her – not her daughter. Having never overcome the trauma of losing his first wife to an accident, which he thinks he was responsible for, he lives in an obsessive loop of guilt and remembrance – and thus, understands, how the past can become the only present for some people, however differing in circumstance and age. He persuades Ritika to allow her mother to be in her past, to respect what she is comfortable in; and instead of yanking her back to the present, to try and make her home even more past-friendly – by surrounding her with the objects (retrieved from a long-forgotten storeroom) that she can identify with. Unfurling these prized items to her on her birthday (which she doesn’t remember) constitute the new celebration that they conceive for her. In the process, they re-connect as a couple.

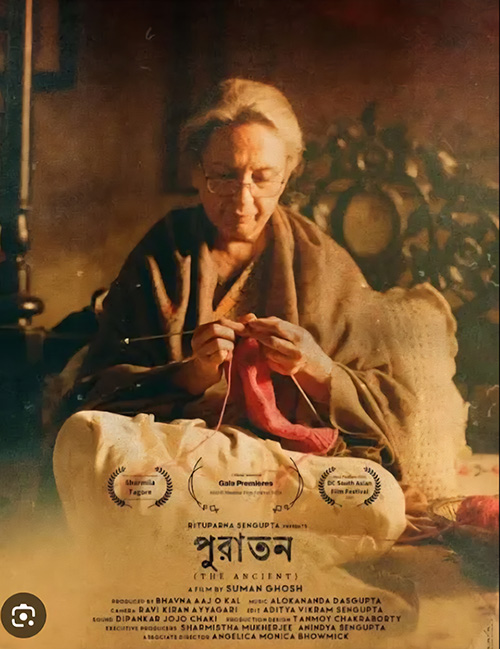

It’s difficult to take one’s eyes off Sharmila Tagore in ‘Puratawn’ – not because of her trademark elegance, but of the conviction with which she manages to become the Everymother of our generation. Women (and men) of my age would all see their mothers in her, I’m dead sure: in the minimal jewellery on her person, the kind of sarees she wears and the way she wears them, the style of her ‘khopa’, the tying of her wet hair with a gamchha, the knitting of sweater for a dear one, the spoiling of the son-in-law with his favourite food, the adamant hoarding of old things (even those she hasn’t touched for decades), and in the perpetual dissatisfaction with the work of the domestic help. She also represents a certain grace – despite all the frailty and vulnerability of old age – that has not been transmitted to the next generation (at least, to my mind).

She will stay with you, long after you’ve watched the film. So will the haunting background score by Alokananda Dasgupta – a rare feat for any Bengali feature, after Ray. [777]