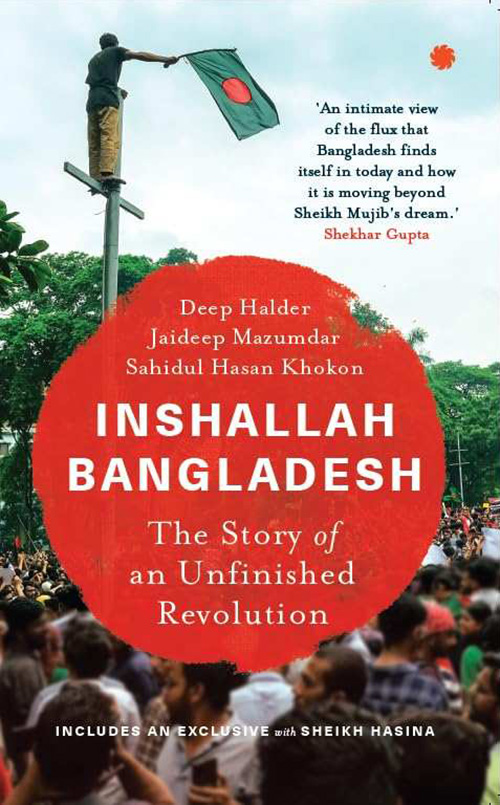

On the front cover of INSHALLAH BANGLADESH: The Story of an Unfinished Revolution – co-authored by Deep Halder, Jaideep Mazumdar and Shahidul Hasan Khokon – is the tagline, “Includes an exclusive with Sheikh Hasina”. That exclusive features in Chapter 7 of the book, summarizing a 13-minute telephonic conversation of the authors with the ousted premier of Bangladesh, in exile in India, on 7 June 2025. Certain sections of it are block quotes; one instance being Hasina spouting a (by now,widely circulated) conspiracy theory:

Don’t call it a revolution! […] It was a terror attack on Bangladesh disguised as a student revolt planned by America and executed by Pakistan. It was done to remove me from power. Whether it was Abu Sayed or other student leaders, the killings were not done by the police. They were killed by terrorists and the killings were passed off as police brutality to turn the public against my government.

The July-August 2024 uprising in Dhaka, to protest against quotas in government jobs, had indeed begun as student protests but spiralled into something none had imagined in such a short span: the toppling of a 15-year regime. What that meant in real terms is explored in the book – from the person in the position of highest authority in the land to its humble citizens. Two striking accounts are given in the ‘Preface’ and Chapter 1 of the book.

On the run, in hiding

Chapter 1 (‘Hasina’s Day Out’)is a blow-by-blow account of 5 August 2024, Sheikh Hasina’s last day at Gonobhaban – the prime ministerial residence in Dhaka – before she was lifted out last-minute in anMi-17 chopper and escaped to India. She had been in denial about the reality of her situation and of the threat to her life (and that of her staff), despite several warnings, until the very end.What lay ahead was an uncertain future for an indefinite time. The ‘Preface’ is the diary of Sahidul (one of the three authors of the book) of the months he spent in hiding in Bangladesh, immediately after the uprising, as he was targeted for being an “anti-national”. His specific crime: he had consistently reported on the rise of fundamentalism in Bangladesh for Indian outlets, India Today among them, where Deep commissioned him to write these stories, leaving behind a digital footprint that now endangered his life.His months on the run – from his own home in Dhaka (leaving his wife and child behind) to first Faridpur and then Jessore (sheltered in both places by BNP leaders), and finally to India(this part ensured by politician Sourav Sikdar, whose grandfather and Sahidul’s were friends in colonial East Bengal) – is the most moving section of the book.

A West Bengali artist had once commented on the narratives of violence in Partition stories thus: “They all follow a similar template – some killed or were complicit, some others saved lives”. It’s the same here. While Sahidul was denied shelter by an influential person he considered close in Dhaka, he was warned and saved by acquaintances-turned-friends made through his work.

Uncomfortable truths & fallible heroes

The 15 chapters of INSHALLAH BANGLADESHare structured under three sections (SOCIETY, POLITICS, PEOPLE), most of which - in some measure - deal with uncomfortable truths about its leaders and the lives of its citizens within the nation (and of some outside). The two chapters that are bravest and most contentious in this regard are in the first section – ‘Mujib: The Man, the Myth’ and ‘Why Young Bangladeshis Hate India’. The reasons for the hate - seen from the youth’s perspective - we are told, are principally three: India’s steadfast support of Hasina “even as she killed electoral democracy in Bangladesh”; its interference in Bangladesh’s internal affairs; and the routine violence perpetrated by the BSF (in the name of crime control) on Bangladeshis on the 4,096-kilometre-long Indo-Bangladesh border (the fifth largest in the world).

Bongobondhu’s life and political career since 1946 come under the scanner in ‘Mujib…’ – with significant focus on his alleged complicity in the Great Calcutta Killings of August 1946 (when he was an acolyte of Suhrawardy); the famine of 1974 during his tenure, which his government failed to contain; and most importantly, his clemency to the Razakars who had sided with the Pakistani army in its genocide of the East Bengali population during the Liberation War of 1971. The analyses of these aspects are referenced with recent works by Sam Dalrymple (Shattered Lands) and Manash Ghosh (Mujib’s Blunders), among others.

While the book looks critically at the founding father of Bangladesh, it doesn’t spare its contemporary leaders as well – both the one ousted and the one currently in charge. Sheikh Hasina’s uninterrupted 15 years in power (‘Good Hasina, Bad Hasina’) and Mohammad Yunus’ 17 months (‘A New Messiah’) are examined in the context of the larger trajectory of their lives: hers, in inheriting the political legacy of her father, in emerging as a strong leader from South Asia, in her shrewd balancing of her strategic allies (India, China and Pakistan), in significant achievements like the signing of the Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord in 1997 (for which she won the UNESCO Houphouet-Boigny Peace Prize in 1998), and in acts of individual kindness and generosity that terribly contradicted her other side – the extermination of all opposition during her tenure, including hundreds of enforced disappearances into secret detention centres (called ‘Aynaghars’) between 2009 and 2021. Yunus’ contribution as an economist for his work on micro-credit, leading interestingly to a Nobel Peace Prize, his long years with the GRAMEEN conglomerate in different capacities, the multiple charges of corruption against him by Hasina’s government, and his new role as Chief Adviser to the caretaker government after the fall of Hasina – all find a place in the chapter on him.

Beyond political reporting & strategic analyses

When three journalists who have long been reporting on Bangladesh come together to write a book on it, in the aftermath of a revolution, it is but natural that the focus would be on politics. While the immediate aftermath of the July-August 2024 revolution (some would prefer the terms ‘uprising’ or ‘upheaval’) is explored at great length in the book, and the leaders of the nation - past and present - scrutinized, a parallel narrative implicated within both is the ideology and history of the three major political parties in the life of the young nation – the Awami League, the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) and the Jamaat-e-Islami – and the constant tussle of power between them, especially the first two. This tussle played out not only during elections, but also in the textbooks that were written in successive regimes where, the narrative of the Liberation War of 1971 was constantly changed, with either Mujib or Lt. Gen. Ziaur Rahman being proclaimed the real hero (depending on whether the Awami League or BNP was in power).

While the Jamaat’s performance in electoral politics has never been substantial, it has, according to the book, emerged as the de facto power – the force behind the continuing, and now accelerated, Islamization of the nation.

One of the chief arguments of the book is that the ideal of secularism – on the basis of which the Liberation War was fought and won – never properly took root in the political life of Bangladesh, because of the ingrained strain of fundamentalism that persisted, no matter who was in power; hence, it’s “the story of an unfinished revolution”. In their brief telephonic conversation with Sheikh Hasina, the authors had told her that what they were “trying to write about were the reasons behind the rise and spread of fundamentalism in Bangladesh before and after the upheavals of July-August 2024 and examination of the roles of major political forces, including hers, to abet or arrest such forces”. The book bears out the truth of this statement. And the fallout of Islamization in Bangladesh - in the widest socio-economic terms - is dealt with especially in the last section of the book: the push for a Hindu Homeland for the increasingly persecuted Hindus (comprising of several south-western districts of Bangladesh); the marginalization of Muslims of less-stringent persuasions – Sufis, Ahmadiyyas, even Sunnis of liberal outlook; the gagging of influential bloggers; and the worst victims of Islamization, always/anywhere – women. All these chapters are told through real life storiesof people interviewed or engaged with in person or long-distance, giving a flavour of the lived lives of citizens that balance out portraits of leaders on the one hand and political/strategic analyses on the other in the book.

But all doesn’t seem to be lost. One of the most hopeful chapters in the book is ‘Can Cinema Save Bangladesh?’. It charts, in part, the career of Shakib Khan (considered the nation’s Shah Rukh) – the icon of contemporary Bangladeshi film industry, cross-border celluloid projects, and the emergence of local OTT platforms like ‘Chorki’ for creating content that push boundaries in storytelling – offering one of the most potent antidotes to repressed lives and gagged voices. The chapter begins and ends with a die-hardfan of Shakib, a little boy named Shamin Hasan Dhumketu – who impersonates the star, long hair and all, for the entertainment of all faiths in a Durga Puja pandal when we meet him first in 2023 in the district of Magura (176 kilometres from Dhaka); and who tells the authors over a call, in 2025, his hair cut short now to imitate his idol’s current style, that things are not well in his village “But I know Shakib Khan will save Bangladesh”!

No matter who saves the nation, Bangladesh should at least preserve a child’s innocence.

Rituparna Roy