If heartache could have a face, it has to be Rekha's – as and in UMRAO JAAN. In the film's second half.

The tawaif

The first half of Muzzafar Ali's classic, based on a novel by Mirza Hadi Ruswa, traces the unfortunate - though not uncommon - tale of a young girl sold to a 'kotha' by an uncle (at a time she was already engaged) and brought up by mercenary women (played by Shaukat Kaifi and Dina Pathak) masquerading as mother-figures who look upon her only as an investment. The father-figures in the brothel - the ustad (Bharat Bhushan) who trains her in music to become a 'tawaif' and the maulvi (Gajanan Jagirdar) who inculcates a love of 'shayeri' in her and encourages her own attempts at it - are, however, the real nurturers. She blooms as a performer and a poet because of their sincere teaching and indulgence.

All the other men in her life fail her: the nawab (Farooq Shaikh) she loves shares her passion for poetry and is besotted with her, but predictably marries the girl of his mother's choice; the dacoit (Raj Babbar) she decides to leave with (without knowing his identity), on the rebound, gives her respect and the promise of a new life, but is shot down by his gang; the companion in the kotha (Nasseruddin Shah), who constantly oscillates between being a flirt and her devoted messenger, is the worst namuna of a parasite; and the younger brother she once loved turns her out when she tries to return home to her mother.

"Kismet nahi, haalatke" (Not fate, but circumstance), she corrects, when it's suggested that all that was happening to her was the rude hand of fate. Watching the restored version of the film in a theatre, decades after seeing the original on TV as a teenager (and listening to its songs endlessly in between) this was what struck me: that the story, though specific to the Faizabad and Lucknow of pre- and post-Mutiny, and to the life and living of a tawaif, could also be seen essentially as a character's lifelong struggle with changing (read, increasingly unfavourable) circumstances and her continual effort to break free. That she finally ends up in the cage that she had repeatedly tried to escape from was her life's greatest irony. But it is not conveyed as a tragedy; rather, as the most dignified option for a courtesan – to earn her living through her art in the home (however exploitative) she was brought up in.

The music

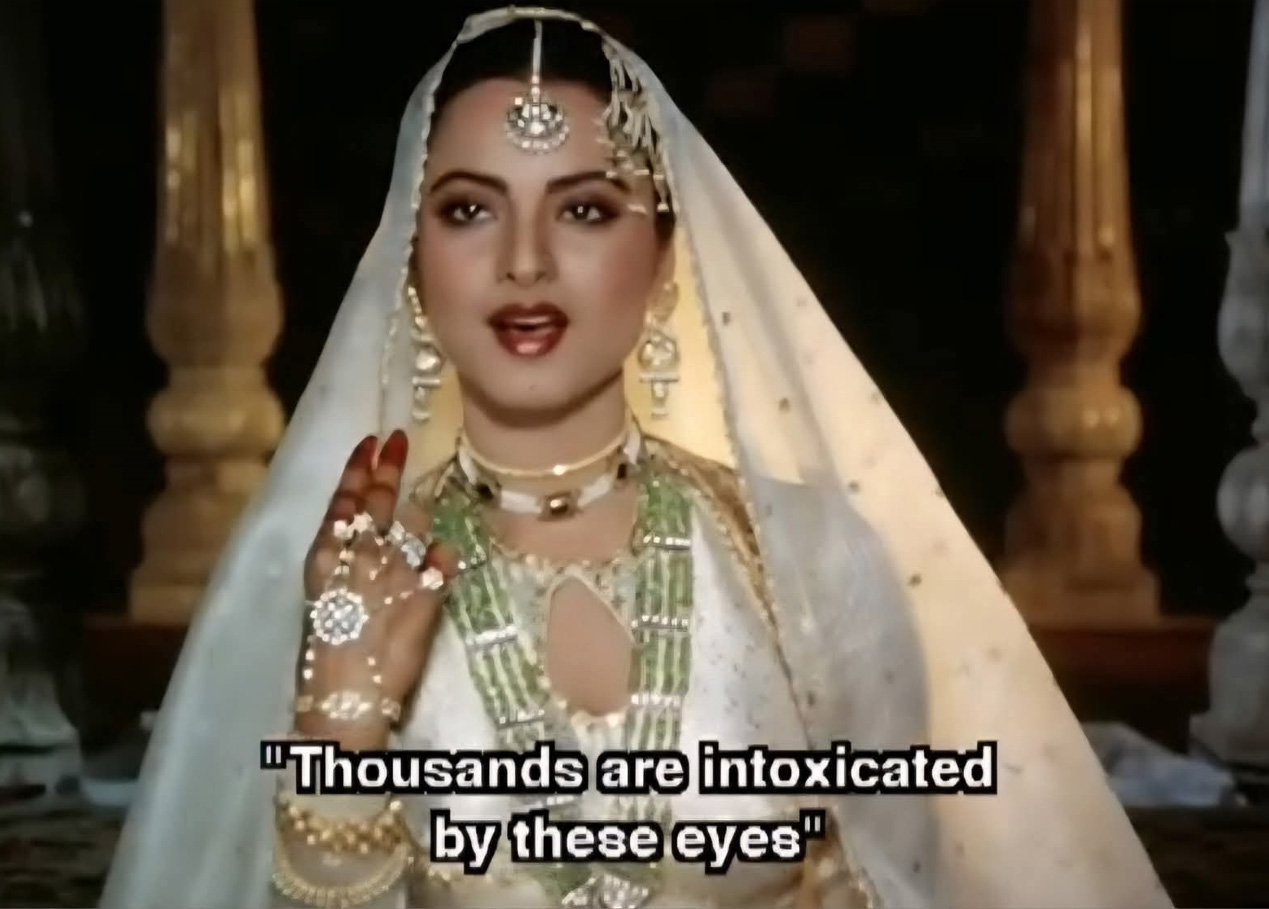

The 'mujras' are the soul of the film. Hema Malini had once said in an interview that she loved doing mujras in films for their gestural richness, where facial expressions and hand-and-arm movements in a sitting posture were as important as the dancing feet. Rekha, as Umrao, epitomizes that gestural richness and languid grace of the mujra – heightened by the unforgettable ghazals in the film, written by Shahryar, composed by Khayyam and sung by the inimitable Asha Bhonsle (in perhaps her career's best performance), which make for the most exquisitely beautiful Hindi-film album there could be! And indeed, in the best tradition of Hindi-film songs carrying the plot forward, we also hear the unfolding saga of Umrao's heart through them: from the sense of abandonment in love ('dilcheezkyahai, aap meri jaan li jiye') and playful seductiveness ('in aankhon ki mastike, mastanehazaronhai') to the heartbreak of having to sing for her married lover and his wife ('justujujiskithi, usko ko tohna paya humne') and the unbearable pain of revisiting the home that could never be hers again ('yeh kyajagehhyandosto, yeh kaunsadayarhai).

Musically, this last moment marks a full circle from the opening engagement song of young Ameeran that accompanies the title credits ('kaahe ko byaahe bides, arrelakhiya babul mohe'). At exactly the midpoint of this beautifully structured narrative, we have the only ghazal in a male voice - the mellifluous Talat Aziz - articulating the bliss of love for the nawab ('zindagi jab bhiteribazmmein, lati haihumain'). It's a transient bliss; and its picturization against the lush backdrop of mustard fields can't help but remind us of another pair of ill-fated lovers romancing in a tulip garden in another film that (though set more than a century later) released the same year (1981), with the same actress playing the beloved.

The actress

The 80s marks the apotheosis of Rekha as an artist. From Hrishikesh Mukherjee's KHUBSOORAT (1980) and Yash Chopra's SILSILA (1981) to Girish Karnad's UTSAV (1984), Gulzaar's IJAAZAT (1987) and Rakesh Roshan's KHOON BHARI MAANG (1988) – she worked in a stupendous array of author-backed roles in a wide range of genres by the most acclaimed directors of her time. Very few in the history of Hindi cinema has been able to match this record.

But Umrao, with her incandescent beauty and deeply imbued melancholy, has won a place in people's hearts that the undoubtedly memorable characters of these other films - the chulbuli sister-in-law, Manju; the wronged beloved, Chandni; the sensuous courtesanVasantsena; the separated wife, Sudha or the avenging widow, Aarti - have not.

As for me, I can watch Umrao a hundred times! [878]